In early March, when the government closed schools and imposed a national lockdown, the lives of millions of Italian children were turned upside down. Since the beginning of the outbreak, more than 300 children have tested positive for the coronavirus, according to the Italian Paediatric Society.

The effects of Covid-19 on children are, in most cases, comparable to a normal flu. But while the virus seems more forgiving towards the young, it can be merciless towards older adults. As of Tuesday, Covid-19 had killed 6,077 people in Italy.

Many children have lost their grandparents or other relatives, while their parents struggle with the virus. The Guardian spoke to a number of Italian children about how they are coping and how they are trying to use their imagination and creativity to fight back against Covid-19.

Andrea, six, Catania

Andrea, who is in lockdown at home with his mother and younger sister, hasn’t seen his father since 2 March. “The doctors took him to the hospital to get well,” his mother told him.

Andrea’s father is one of more than 230 Covid-19 patients in hospital in Catania, Sicily. In anticipation of seeing him again, Andrea’s only way to express his affection is to make drawings, which the doctors have dutifully delivered to his father.

In one of these, Andrea imagined how to stop the spread of coronavirus. In his imagination, someone mistakenly opened the door to the dimension that separates our world from the virus. It’s not easy to close it again, but SuperAndrea and SuperDad are up to the task, shielded by the energy of a giant, sparkling heart that coronavirus can’t penetrate. But the door won’t be closed until his father is discharged from that cursed hospital.

“Hi, Daddy. I hope you feel better. I love you a lot and hope you get well so we can play again,” Andrea wrote in a recent message, adding: “If we don’t want coronavirus to get stronger, then we have to stay home,” Andrea wrote on a piece of paper entitled My Thoughts on Coronavirus, in which he calls out to all Italians: “Don’t eat too much. Otherwise you’ll have to go out to get groceries, and then you might get the virus if you leave the house.”

Michele Passalacqua, six, Palermo

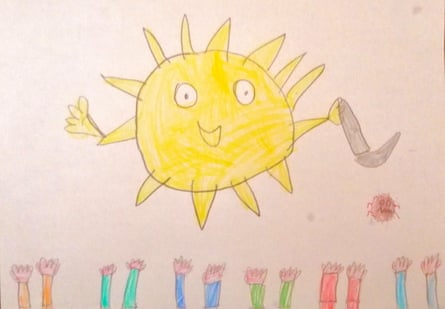

People in Italy’s southern regions are bracing themselves as the number of confirmed coronavirus cases grows daily. In locked-down Palermo, Sicily, Michele has already found a cure for Covid-19.

“It’s a magic potion. You see, coronavirus is a small little creature, almost invisible. You can only see it using a microscope. It can jump from one spot to another. And there’s not just one. It can multiply. We have to use the magic potion to hit the biggest of them, the coronavirus monster that brought them to life. If we splash it with the magic potion, then all the other viruses will die.”

And if Michele’s strategy doesn’t work, he already has a plan B: the sun. Even if the World Health Organization hasn’t confirmed that higher spring temperatures might weaken the virus, Michele knows that the sun will kill it. “It’ll use a flaming sword,” he says. “Unless I discover the potion first. I’m even starting to get bored here in the house. Fine, I don’t have to go to school every day, but I miss my friends and classmates.”

Marco, nine, and Jacopo, three, Lozzo Atestino

Marco and his younger brother live in Lozzo Atestino, in the province of Padua – one of the first Italian cities hit by the virus. The two brothers and their parents have all been ill with Covid-19.

Marco wrote to the Guardian: “Unfortunately, my little brother and I had the bad luck of getting to know the coronavirus. Everything started on 20 February, when we found out the virus had arrived in neighbouring towns. Mum tried to reassure me by saying we’re all healthy, but a few days later she got sick and I was worried and sad.”

While the children haven’t shown serious symptoms, their parents got increasingly unwell until they needed to be taken to hospital. “That was the worst day,” Marco says. “I remember we were in the ambulance and my mum wasn’t breathing well. My little brother started crying. When we arrived at the hospital, I started crying too because I thought they’d have to take us away from our parents.”

Fortunately, that didn’t happen, and from that point on Marco and his family began a long period of quarantine that is still under way. “The days go by and we can’t have any contact with anyone. Mum orders groceries using the phone, and they leave the bags outside at the gate. I see my grandparents, aunts and uncles on video calls.”

While waiting for the results of the next round of tests, Marco and his brother see the outside world through a large window in their home. “I can’t wait until coronavirus will just leave us in peace,” he says. “I can’t wait to go and play outside. But if there’s one thing I learned, it’s the importance of health and the love of my family.”

Greta, six, and Riccardo Gabanelli, four, Bergamo

Coronavirus has pushed the city of Bergamo, Lombardy, to its limits; there aren’t even enough coffins to transport the dead. A thousand people have died here since the outbreak of the crisis. Crematorium ovens are unable to keep up, and the armed forces have to transfer the bodies to other cities.

Greta and Riccardo have run out of paper, when drawing is one of the most important activities that keeps them busy while shut in their home. For weeks, Italians have been hanging large paper sheets from their windows with a rainbow and the phrase “Andrà tutto bene” (everything will be fine).

Greta and Riccardo wanted to make one, too, but they can’t buy paper because shops are closed. To join in the movement, they managed to glue four precious sheets together. But as the days drag on, the children’s nerves are on edge. “I feel really bad, I get bored too much, and nothing’s getting better,” Greta repeats to her mother.

Francesco Giuffrida, eight, Bologna

In Bologna, in the region of Emilia-Romagna, things are no better. There are more than 7,000 cases of coronavirus here, and 800 people have died. Francesco has no intention of giving up. He sees the emergency as a struggle between David and Goliath. David represents the humans. Goliath, the coronavirus, says: “I’m going to infect the whole world!” How can such a small creature like David defeat the virus?

Francesco has no doubt. The weapon people have to defeat the virus is the same strength that has been uniting Italy: “You won’t be able to infect the world as long as there’s humanity!”