(John McCann/M&G)

In his re-released and excellent biography Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues, Bryan Rostron makes a usefully awkward point in his Afterword about how the lives of victims of apartheid-era crimes are not equal. The apartheid state killed, abducted, tortured, assaulted and maimed tens of thousands of black South Africans. Yet when we speak of these victims, all but a handful of them are remembered, publicly, with empathy and with a sustained interest in justice for them and their families.

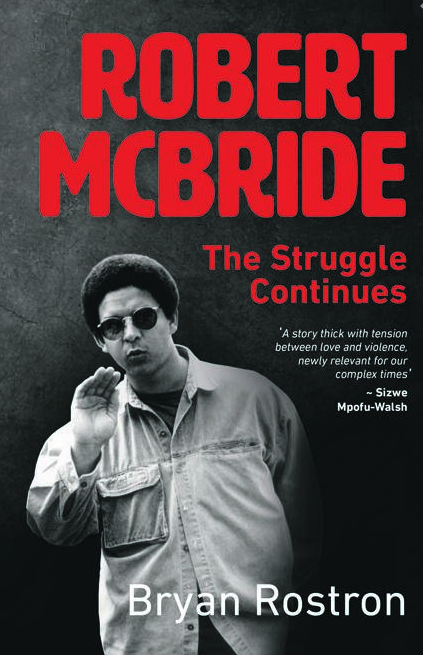

Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues (Tafelberg)

Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues (Tafelberg)By contrast, few white people were killed or had their human rights violated during that period, even while adjusting this trite fact for the reality that white people obviously constitute a racial minority. And yet a name like Robert McBride stirs deep emotions, and hatred even, among many white people.

Rostron, puzzling through the sustained anger of many white people about the Durban bar bombing that killed civilians, for which McBride was sentenced to death, writes: “It is entirely understandable that [the three young white women’s] relatives and friends should harbour embittered feelings, even thoughts of revenge. The brother of one of the women even planned to try and kill McBride, but never carried out his plan. But for other white people, in the context of a brutal war, why do they cling to this one act to the exclusion of other, considerably more lethal atrocities that occurred on a regular basis?”

He cites, to take but one of many comparable cases of violence meted out against black people, the massacre in October 1993 of five teenagers asleep in a house in Mthatha, a massacre that was authorised by then president FW de Klerk. Most white people permanently angry about the Magoo’s Bar bomb do not emote angrily about the lost lives of innocent black people such as those teenagers from Mthatha.

Rostron goes on to say: “Out of all the many thousands of black civilians killed by South African apartheid police and servicemen, the Magoo’s Bar bomb remains a habitually unforgiven fixation.”

One lazy view of what Rostron is getting at here is that killing civilians is morally defensible. His point is not, as I read him, to take a view on what counts as a just war, nor to take a view on what the permissible strategies and tactics to achieve a just outcome are. He simply observes how racialised even our moral outrage is when innocent people are caught in crossfire. In that regard he is surely right?

Another lazy response to Rostron would be to argue that all lives matter, and that he is interspersing his biography of McBride with an Olympics of suffering. This kind of response would be a refusal to read him accurately, because to do so might result in you having to examine yourself, which you might not be ready to do.

What we are invited to reflect on is how no one is immune to identity politics, including white South Africans and self-styled progressives and liberals. If you have a strong view about McBride and think him the epitome of violent evil, but you think that De Klerk’s legacy can be subject to reasonable disagreement between reasonable people, then you are exposing your own tribalism that you do not own but forms part of the tribalism that you delight in accusing others of peddling.

White people, too, can be and often are tribalistic. That is why many white people know of the Magoo’s Bar killings, but not of other sites such as the Mthatha massacre. This brings me to the broader issue, which is the business of unfinished apartheid business.

I don’t think there can be any South Africans who can declare themselves to be healed from the scars of the past; they are way too deep. Because we have an impulse to think of our individual selves as fundamentally decent and healthy, few of us have the self-knowledge or courage to recognise the consequences of political trauma to ourselves.

It is easier to observe and talk about national trauma at the level of society. That is safe territory. It is impersonal. We can participate in that conversation as pop psychologists opining about psycho-political movements in society, rather than focusing on our private wounded selves. In my view, a lot of contemporary South African struggles are worsened by this complex unfinished business.

A colleague wondered aloud, after a radio interview this week, whether, for example, men who fought on the side of the liberation movements against the apartheid state received counselling when apartheid ended. We know this did not happen as a matter of course. White conscripts brutalised by the apartheid state also came back from immoral border wars with unattended psychological wounds and many unmet needs.

These men are our brothers, cousins, fathers, uncles, mentors, bosses, husbands, boyfriends, business partners, public office bearers, captains of industry and so forth. It is of little wonder that we are a violent lot. I am not just referring to the much talked about gratuitous violence of the crimes we focus on publicly, but also the more expansive forms of violence, including gaslighting, toxic machismo, bullying, verbal and psychological terror, quite apart from overt physical violence.

The wounds of apartheid have morphed into relabelled “contemporary” problems such as “unjust workplaces”. Actually, when you did not deal with your post-traumatic stress disorder and now have positions of power in politics, business or civil society, you are a danger to yourself and to others. That is a big part of our collective unfinished business we have not dealt with as a society.

We should, of course, also be kind to ourselves. When we have obvious material and structural economic problems to solve for example, such as a stagnant economy and unemployment, then it seems a luxury to talk about psychology. But we cannot afford to underestimate the material cost of this kind of thinking.

There is a connection, in part at least, between some of our historical wounds and the immediate drivers of our more pressing current concerns.

For example, we need quality leaders in business, civil society and in the state to allow for effective strategic co-operation across our various interests. We have a dearth of leadership excellence in these strata. One reason for this is precisely that too many men, in part shaped by the violent apartheid state that raised us, enter negotiating forums as if these are modern versions of border wars. You cannot ignore what apartheid psychology has done even to our ability to work together in 2020.

Which brings me back to the Magoo’s car bomb and Rostron’s observations about racialised responses to it. One of the most unforgiving effects of apartheid is that we often refused to see each other as fully human. We were socialised to believe that skin colour is an information-bearing trait. I see Eusebius, he looks coloured, and therefore must be so, and I can know him before I have interacted with him.

He might surprise me, of course, by defeating assumptions I bring to our interactions. But those assumptions are alive in my belief-set until they have been defeated.

Many would pretend otherwise, but I call that bullshit. We still experience this kind of sullied social reality. We need to separate what we desire from what is reality. In my first book, A Bantu In My Bathroom (2012), I wrote of a white friend who told me, years into our friendship, that when he first met me as his first-year philosophy tutor, his immediate thought as I walked into the tutorial room was something like: “Oh God, I got the affirmative action one!”

He carried assumptions about my competence based purely on my skin colour. He only dislodged the assumptions once I opened my mouth. White tutors, by contrast, are assumed to be qualified unless and until they let you down. To be assumed to be excellent is itself a form of white privilege.

These are among the hangovers of apartheid logic playing out at a discursive, but also at social and psychological levels. We avoid the awkward and hard work of thinking and working through these historical scars, and making sense of what they mean for interpersonal and professional relationships in contemporary South Africa.

It would be a mistake to declare ourselves okay. We need to self-examine, honestly, and be prepared to complete the work that could never have ended with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. We remain a wounded lot with many unmet needs and that will continue to cost us if we are not courageous enough to confront these issues.