Billie Eilish’s mother is apologizing for the messy house. “We’re just back from tour,” explains Maggie Baird at the door of their little bungalow in Highland Park, just east of the Los Angeles River. Indeed, her daughter’s pop stardom has seemingly hit the family home like a tsunami. Tour luggage is by the door, unsure of whether it’s coming or going. The dining room looks like a Hot Topic stockroom after a burglary, with stacks of merchandise boxes containing flashes of neon-green shirts and sweaters. A container of heavy silver jewelry is on the floor next to a book of Rupi Kaur poetry. Eilish’s keyboard is now a storage table, and her brother Finneas O’Connell’s piano also looks out of commission, barely visible amid the jumble. A closer look reveals a book of Green Day sheet music, a rhyming dictionary, and...is that a bed?

It is. Behind the hallway piano is a bed where Baird and her husband, Patrick O’Connell, sleep when they’re not touring with Eilish. It’s where Eilish and Finneas once slept; the four of them shared it until Finneas was 10. After that, the siblings moved into two bedrooms in the back of the house.

It was in those rooms that they wrote, recorded, and produced Eilish’s music, including her debut studio album, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? It went to number one after it was released in March, and since then, it’s returned to number one a total of three times. But stats like these are becoming standard fare for the 17-year-old.

Eilish’s songs and videos have been streamed more than 15 billion times. She’s completed four sold-out North American tours with Finneas, 22. In July, she put out a new version of her hit “Bad Guy” with a cameo from Justin Bieber, and less than two weeks later, she was nominated for nine MTV Video Music Awards. Yesterday afternoon, she released the official video for "all the good girls go to hell." By nightfall, it had been viewed over 5 million times.

Dave Grohl has famously likened the frenzied reaction to that of his first band: “The same thing is happening with her that happened with Nirvana in 1991.” But her success feels too new to really be compared. She’s the first number one artist born this millennium, and too young to have ever owned a CD. She’s the youngest female star to top the charts in a decade, and the only one ever to have 14 simultaneous chart entries. She’s more than a cultural upstart; she’s seemingly the answer to a dying industry.

Eilish is neither the commercially Napoleonic Taylor Swift nor an insomniac version of girl-next-door Britney Spears. She is the sister and daughter of something closer to homegrown. She is Billie Eilish before a hit song or an album campaign—a person before a phenomenon.

It’s 11:45 a.m., and Eilish is in the kitchen. You can hear her roar (“Argh!”) every time Baird opens the door to check up on her as she FaceTimes a child with leukemia for the Make-A-Wish Foundation. The house may be her empire’s HQ, but it’s keeping her humble. There’s only one poster on the wall and one framed review from the Los Angeles Times. Both are for the 2013 movie Life Inside Out, which Baird—an actress—cowrote and starred in, opposite Finneas. Eilish still lives at home, but Finneas recently moved out, a few miles away. Their bond seems unbreakable.

When she gets off the phone, Eilish attacks like a friendly Rottweiler.“Hello!” she says, almost jumping in the air. She’s not as mobile today because she’s finally resting her sprained ankle—one of countless injuries incurred from her onstage pogo-ing. “Ew!” she says about injuries.

You’d never know she was in pain. Outwardly, she’s as hard as her fake nails, which go clickety-clack on the kitchen table as she reclines in her seat. They’re fluorescent green and pointed like stakes used to slay vampires. She sits like a cat, preening them through her mane. She prods them into her ear canals; she flicks them on their sides when removing sleep from her eyes. The other day, she made a hole in her left hand with one of them while riding a horse.

“I stabbed myself,” she says, demonstrating how it happened. “Whatever. I love these nails, but I’m gonna change the shape because I don’t wanna accidentally poke a horse in the face.”

Eilish has been home for three days. She left in the spring, and now it’s summer. “That’s super fucking weird,” she says. “It feels like it’s gone by in the blink of an eye. It also feels like it’s taken 400 years.” Eilish’s tour feels more like a global crusade. She’s just done a run that’s taken in two momentous Coachella sets, a breakthrough Glastonbury slot, and three sold-out hometown shows, including the Greek Theatre. At all these performances, Billie mania gripped her fans’ faces like late-’90s Spice Girls fever—their screams could have echoed in space. And Eilish’s firecracker energy feeds off it. At Coachella, the wind was so strong, the palm trees on either side of her looked as if they might snap, but she remained a statue of defiance: “Ha-ha, I almost fell over!”

She admits, “This was the first tour I enjoyed. That means I haven’t really enjoyed the rest of them.” The earlier tours were stressful. Eilish’s meteoric fame became too great for her environment; the smaller venues weren’t equipped to keep her safe. Sometimes it wasn’t smart to meet fans outside. “When there are a thousand people outside, nobody’s going through security; I don’t know that you’re all here for me, or for good things. It’s such a bummer.” She has security now, and the venues are bigger. She also brings friends on the road. “I need people. I’m a people person,” she says. “For a while, I would be gone for months and wouldn’t see my friends. I’d come back, and they wouldn’t be friends with me anymore. That’s not their fault. You’re not gonna forget me, but you’re gonna forget what it felt like to love me. It sucked.”

The way Eilish performs sets her apart from mainstream pop stars predating her. Her shows aren’t about displaying her voice perfectly or fabricating some fantastical escape from reality. They’re a place where Eilish can unpack her truest emotions onstage. The energy is more like a hardcore show than a pop spectacle.

Onstage, she’s pushing through barriers of extreme physical pain. “I would rather not do a show than do a mediocre version. I am one thousand percent serious,” she warns. Eilish sprained her ankle the day of her biggest L.A. show. “Trash,” she says. “I’m telling you: I’m never going to cancel a show the day of. If I do, someone is allowed to slap me in the face. If I die? Okay, I get it. Buck up, Billie. Get the fuck up on that stage, and do your shit.”

On her European tour in February, Eilish got shin splints in both calves.

She pulls up her bruised legs to show me where it hurt the most. It still hurts. “It’s the most agonizing thing. The more I treated it, the worse it got. I am a really stoic person, which is why I get injured so much,” she says. “I never say when things hurt. I don’t complain. I don’t like being high-maintenance. I don’t like showing pain. I don’t cry. Ever. But there are some pains that choke you up.” She puts her hands around her throat to show what she means.

While in Manchester, nothing alleviated the pain, so she tried acupuncture. “Acupuncture’s not supposed to hurt, but every single needle felt like a knife. Chk-chk-chk,” she says, making stabbing noises. She couldn’t even stand up. Come showtime an hour later, however, it was a different story. “My adrenaline,” she says, laughing. “My adrenaline’s like Hulk, dude.”

Her music is emblematic of this: soft and jazzy in her voice, but couched in hard-driving, beats-driven production. That’s the way teenagers have to be now—steely on the outside, but tender at the core.

She’s praised for not sugarcoating teen life. She sings about California burning in the wildfires. She sings about self-loathing. She sings about toxic love. It’s difficult for Eilish to gauge the root of the connection between herself and other teens. “I don’t know what it feels like not to be a teenager,” she says. “But kids know more than adults.”

Eilish says she grew up with very limited means. Born in downtown L.A., she and Finneas were homeschooled and raised as pragmatists in Highland Park. Eilish worked part-time at a horse barn, and the place is now her only sanctuary from being Billie Eilish. “Horses are the most therapeutic animals,” she says. “Horses and dogs. And cows, dude. People eat those—that’s crazy.”

But she has always performed. There’s a video of seven-year-old Eilish singing “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” onstage. She pouts through the song with her arms folded. You can hear her musical upbringing in her oldies voice, with its echoes of everyone from Frank Sinatra to Peggy Lee. As she got older, Eilish deliberately searched for unpopular music on SoundCloud, and she studied rappers. “I’ve always been a music listener. It’s crazy to me that people only find music by going to the most popular hits,” she says. “What the fuck are you doing?”

She says she prefers listening to music to making it. Conveniently, her brother is the opposite. Old home videos show Eilish doing hand-stands in the living room while Finneas plays the piano. “He wanted to make music, and I liked feeling it, singing to it, listening to it.” Performing to it? “Yeah,” she says.

She started writing her own songs at 11. When she was 13, Finneas asked her to sing on a track called “Ocean Eyes,” which they uploaded to SoundCloud. After she signed to Interscope in 2016, the label put on a small showcase for her in its offices. She was 14, and Finneas backed her. I was invited; I remember that she played a ukulele. There were a lot of men around, but Eilish seemed unimpressed by adults. To this day, she seems uncompromising. Even the ukulele remains on the album’s track “8.” How has she maintained her autonomy? Eilish does whatever she likes.

“When you’re trying to come off a certain way, it’s not gonna work,” she says. The notion that she’s built a career as an anti-pop pioneer tickles her. She understands the conversation, but the rebel narrative wasn’t one she sought.

“I was just making songs with my brother. Now it’s like a thing: I’m this artist who’s going against the whatever-the-fuck.” She puts her hands up. “Where?! I wasn’t saying, ‘Fuck pop!’ I was just making what I wanted.”

Billie Takes Over Spotify's Teen Party Playlist

The proximity and safety net of her family are key. Historically, families are presented as the opposing force to a teen star’s autonomy, but in her case, Eilish’s power is fueled by them. “I’m lucky to have a family that I like, and that likes me,” she says. “The only reason I do what I do is because my parents didn’t force me. If they’d said, ‘Here’s a guitar, here’s a microphone, sing and write,’ I would have been like, ‘Goodbye! I’m gonna go do drugs.’” Baird laughs from the front room. Eilish adds: “You can’t get mad at kids, bro. People have some shitty families. I’m kinda shocked my parents are still together. I’m not at all trying to brag—I’m just trying to say, I feel for the people who don’t have a family that wants them to be happy in their lives.”

The celebration of Eilish as a bastion of truth has its pitfalls—one of which is boundaries. Last year, she decided to quit Twitter (“the best decision of my life”). She’s recently been open about her therapy and struggle with Tourette syndrome. During her lowest mental health bouts, she says, Twitter became a trigger. “I was in Europe, in one of the worst headspaces I’ve been in. That’s when I realized, ‘You know what? Bye!’ There are so many things I can’t stop, but I can delete Twitter.” On Instagram, it’s easier to ignore comments. Twitter is nothing but comments, and she found herself looking at every one. “I have too much love for myself—I don’t need to see all these opinions. Shoo!”

What does a bad headspace look like for Eilish? Does the constant sharing by fans who also feel lost and isolated keep her in a negative mindset? She takes a moment to think.

A few days ago, Eilish wrote something down to share with friends, and it describes a new feeling.“I’m finally—” she says, hesitating. “I’m finally not miserable.” When Eilish looks back at interviews, even from the start of this year, it reminds her of how much she was suffering.

“Two years ago, I felt like nothing mattered; every single thing was pointless. Not just in my life, but everything in the whole world. I was fully clinically depressed. It’s insane to look back and not be anymore,” she says. Some cynics have accused her of faking depression. “It hurt me to see that. I was a 16-year-old girl who was really unstable. I’m in the happiest place of my life, and I didn’t think that I would even make it to this age.”

That’s quite an admission. “Pff!” She laughs. “If I’m being honest....” There’s a silence over the table, and it happens. “I’m literally, like, gonna cry.” And she starts to cry.

Happiness is a “crazy” feeling, she says. “I haven’t been happy for years. I didn’t think I would be happy again. And here I am—I’ve gotten to a point where I’m finally okay. It’s not because I’m famous. It’s not because I have a little more money. It’s so many different things: growing up, people coming into your life, certain people leaving your life. All I can say now is, For anybody who isn’t doing well, it will get better. Have hope. I did this shit with fame riding on my shoulders. And I love fame! Being famous is great, but it was horrible for a year. Now I love what I do, and I’m me again. The good me. And I love the eyes on me.”

There are many of those, I say. “There are,” she nods. “There are more now.”

Baird says she has to go out, and Eilish looks confused. “Where are you going?!” Once this is wrapped, Eilish will be home alone for the first time in a while. Does she like having free time to herself? “Yuck!” she says. “Days off are gross! What the fuck do I do now? I don’t like being bored. I don’t like being lazy. Even when I’ve got a fucking sprained ankle and I’m sick. Bleurgh! Eurgh!”

Eilish can’t go out in the neighborhood. “No, I can’t go anywhere,” she says. “But that’s okay. What am I gonna do? Go get some soap? At some store? Ha-ha, I’m good.” Sometimes she wishes she could press a button and stop it all for 10 minutes. “When I go to the airport,” she says. “I wish I could turn it off then. When I’m in the plane and two girls come and tap me on the fucking face and take a picture of me while I’m trying to sleep. Don’t get me wrong—I love every person that gives any fucks about me. But there are lines. People forget what respect is.”

Speaking of: Respect is an issue when it comes to the discussion of Eilish’s body. She physically yawns when the subject is raised. Her style—over-size shorts and shirts—is subject to memes. Feminists theorize that she’s desexualizing herself; parents thank her for covering up because, in turn, so do their daughters. “You’re missing the point!” she cries. “The point is not: Hey, let’s go slut-shame all these girls for not dressing like Billie Eilish. It makes me mad. I have to wear a big shirt for you not to feel uncomfortable about my boobs!" Before a show in Nashville in June, she climbed off the bus in a tank top to greet fans outside. Someone took a picture of her. "My boobs were trending on Twitter!" she shrieks. "At number one! What is that?! Every outlet wrote about my boobs!" She's a minor, and even CNN wrote a story about Eilish's boobs.

“I look good in it,” she says, laughing. “I was born with fucking boobs, bro. I was born with DNA that was gonna give me big-ass boobs.” She says her breasts have been an issue for as long as she can remember, which is why she covers them. “I was recently FaceTiming a close friend of mine who’s a dude, and I was wearing a tank top. He was like, ‘Ugh, put a shirt on!’ And I said, ‘I have a shirt on.’ Someone with smaller boobs could wear a tank top, and I could put on that exact tank top and get slut-shamed because my boobs are big. That is stupid. It’s the same shirt!”

A few months from now, Eilish will be 18. “I’m gonna be a woman. I wanna show my body. What if I wanna make a video where I wanna look desirable?” she asks before covering her tracks. “Not a porno! But I know it would be a huge thing,” Eilish protests. “I know people will say, ‘I’ve lost all respect for her.’ ” There was once a comment beneath a video of hers that’s stuck with Eilish. It said: “Tomboys always end up being the biggest whores.” She was wearing big shorts and a big T-shirt, but her crime was in slightly grazing her boobs with the back of her hand by accident. “I can’t win!” she howls. And she howls like a really happy kid.

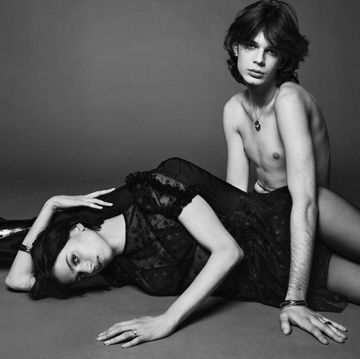

Styled by Anna Trevelyan. Hair by Tammy Yi for Leonor Greyl Paris; makeup by Robert Rumsey for Westman Atelier. Manicure by Jolene Brodeur for OPI; set design by Bryan Porter at Owl & the Elephant; produced by Paul Preiss at Preiss Creative.

This article will appear in the October 2019 issue of ELLE, on newsstands September 26.