WASHINGTON — Since it arrived in the United States, the Covid-19 virus has been a national story that is felt at the local level. Different communities have experienced the worst of the pandemic at different times. The pandemic started as a coastal story back in 2020, but it wasn’t long until it moved into the country as the virus spread.

Now, the omicron variant could take those local differences to new heights, driven by discrepancies in vaccination rates and hospital availability, and the data suggests that rural communities, in particular, could be headed for some hard weeks ahead.

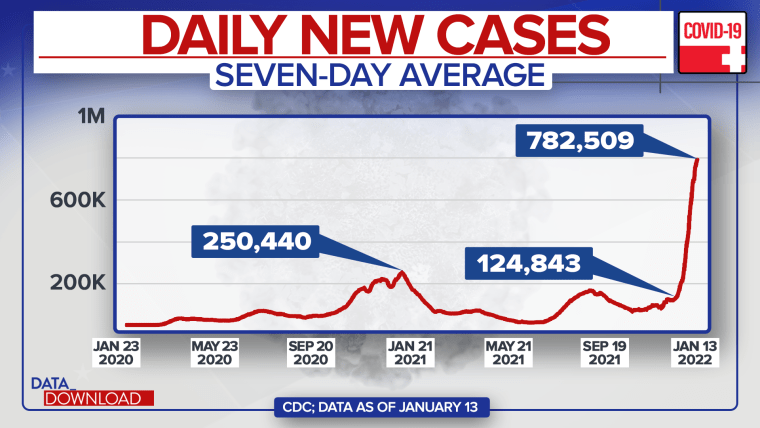

For weeks now, the national Covid figures have been a focus of news stories and for good reason. The spike in new cases has been unlike anything the country has experienced so far in the pandemic.

One month ago, the nation was averaging about 125,000 new Covid cases a day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By the middle of last week, that average new case figure was about 783,000 a day. That’s more than a six-fold increase new daily cases in that time.

And to put those figures in perspective, last year at this time (in the 2021 post-holiday surge) the highest average new daily case number clocked in at about 250,000 a day, less than one-third of what the number is today.

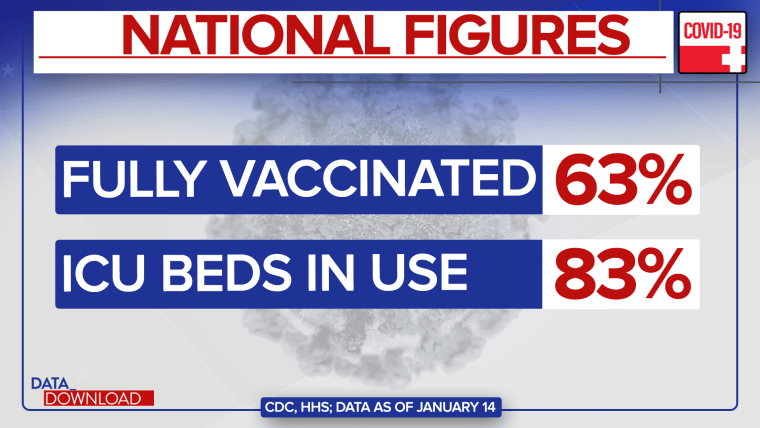

Some note that this latest, highly transmissible variant has spread even after millions of Americans got vaccinated, but doctors argue those vaccinations have helped.

Today, about 63 percent of the nation’s total population is vaccinated. That might be one reason why even as cases are spiking, deaths are remaining relatively flat.

And even while much of the nation’s supply of intensive care unit beds are filled today (about 83 percent are in use, according to the Department of Health and Human Services), considering the size of the current spike, the numbers could be worse.

Some of that relatively good news on Covid, however, may be due to where the current spike in cases is hitting hardest.

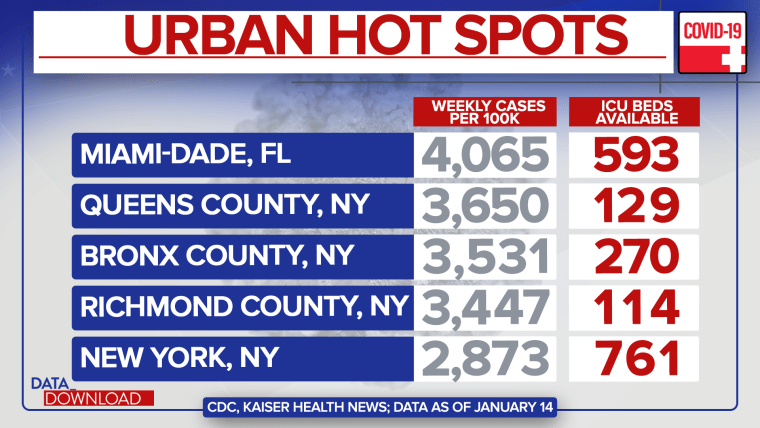

Much like the beginning of the Covid pandemic, the early stages of omicron are mostly tied to urban areas, particularly the New York and Miami metro areas.

Nationally, the weekly figure for new Covid cases per 100,000 population stands at about 1,650 people. But in Miami-Dade County, the figure is over 4,000. In New York City’s borough of Queens, it’s 3,650 new cases this week per 100,000 people. In the Bronx, it’s 3,531 per 100,000. In Staten Island, it’s 3,447 and in Manhattan it’s 2,873.

In other words, those urban counties and others like them are really driving the nation’s omicron numbers so far. Why? They are more likely to have people traveling in and out of the United States than other communities (they have large international airports and foreign-born populations) and they are densely packed with people (making it easier for omicron to spread once it gets into one of those communities).

However, all of those counties also hold some advantages compared to the nation at large. They are all above the national average for vaccination rates and they all have a decent number of ICU beds available — Miami-Dade and Manhattan in particular.

So, in a sense, they have been exposed to the worst of omicron first, but they also have some built-in ways to combat it.

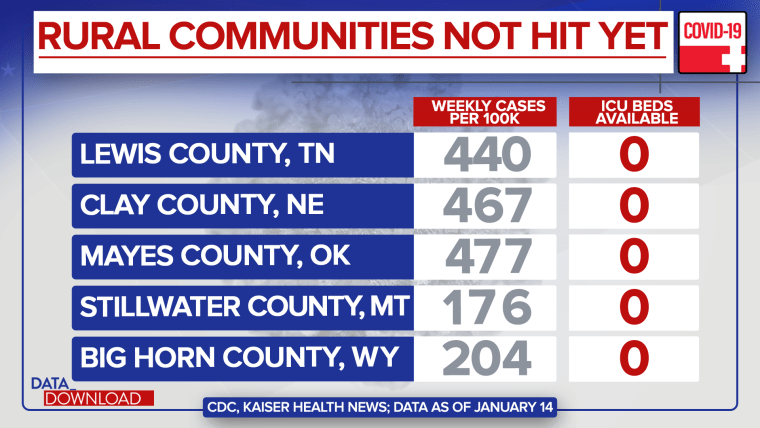

Other parts of the country still might be weeks away from their high point in the omicron surge, but they don’t hold those same advantages. Consider a scattering of rural counties.

Mayes County, Oklahoma, has a rate of only 477 new weekly cases per 100,000 population — less than a third of the national figure — but only 42 percent of its residents are fully vaccinated. In Clay County, Nebraska, the new weekly case rate in 467 per 100,000 and only 40 percent are fully vaccinated. In Lewis County, Tennessee, the figures are 440 per 100,000 and 35 percent vaccinated. In Big Horn County, Wyoming, it’s 204 and 37 percent. And in Stillwater County, Montana, it’s a rate of 176 per 100,000 and 41 percent vaccinated.

None of those counties have ICU beds in them and hundreds of rural counties are in the same boat.

As it often is with Covid, none of this certain. There are a lot of unknowns. How much of omicron’s “milder” symptoms are due to vaccination and how much are due to the nature of the variant? Could the more spread-out nature of rural places offer an additional defense against omicron?

But there are also some knowns here. Many of the nation’s rural counties have far lower vaccination rates than their urban counterparts. And if there is massive spread in rural communities, there simply are not a lot of rural hospitals to serve people, never mind ICU beds. Add in the fact that many rural communities tend to be home to older populations and the situation only looks more troubling.

Much of the hopes about omicron rest on the pattern it has shown in other countries — cases spike and then quickly fall off. That still may be the case in the United States, but for some communities it may not hold much comfort. The timing, size and impact of those spikes will likely vary dramatically with rural communities taking a hard hit in what could be a long hard winter.