Personality

Can a Person Have More Than One Personality Disorder?

... and why simultaneous intervention is critical.

Posted November 26, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- It's not unusual for patients to exhibit mixed personality disorders or meet full criteria for two or more.

- Personality disorders, even those in different clusters, often have etiological similarities.

- Treatment for mixed personality disorders requires simultaneous intervention, as conditions become symbiotically pathological.

It's no secret that some personality disorders (PDO) have significant similarities. The Narcissistic and Antisocial share a lack of empathy and tendency for rage; Borderlines and Dependents have profound fears of abandonment and clingy behavior; the Schizoid and Avoidant are socially anxious and unassertive.

Despite the glaring similarities, careful differential diagnosis can yield one "pure" personality disorder. However, it's most common that patients exhibit a mixed presentation (APA, 2013) such as Antisocial with some Paranoid PDO characteristics, or in fact meet full criteria for two or more PDOs (e.g., Grant et al., 2005; Millon, 2011; Skewes et al., 2015).

Readers familiar with PDOs may notice that the above examples are both intra-cluster and inter-cluster (see below regarding personality disorder organization). Indeed, the PDO cluster boundaries are permeable. Grant (2005) noted that this is common, with both inter- and intra-cluster PDO combinations being "... pervasive in the general U.S. population."

Personality Disorder Organization

Generally, personality disorders are categorized under three different umbrellas, or themes, and the collection of disorders under each umbrella is called a cluster. They are arranged in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) as follows:

- Cluster A are PDOs with a semi-psychotic theme. These include the Paranoid, Schizotypal, and Schizoid.

- Cluster B are PDOs with a common theme of dramatic behavior/entitlement/moodiness/poor impulse control. This includes the Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, and Narcissistic.

- Cluster C are PDOs with an anxious-depressed common theme. Here we find the Avoidant, Dependent, and Obsessive-Compulsive/Perfectionistic.

Basically, each cluster is organized around a theme, and their respective disorders are particular expressions of that theme.

Given the conditions within clusters share a theme, it's easier to see how they often readily mix (Turner, 1994). Common intra-cluster co-occurrence includes mingling traits and characteristics like a mixed Borderline/Narcissistic or Avoidant/Dependent presentation. As previously noted, however, the clusters, though they present polarities in themes, have porous boundaries, which will be explored further below. Some common inter-cluster presentations are Narcissistic/Obsessive-Compulsive, Borderline/Avoidant, and Borderline/Dependent. Researchers Wongpakaran et al. (2015) found the most common PDO mix, however, seems to be Cluster A and C, such as Schizoid/Avoidant.

It's important to bear in mind, though, that mixing and matching PDOs isn't a free-for-all. Some are so polar-opposite that nothing about them could co-exist. A Histrionic, for instance, preferring to be the center of attention at any cost, is in stark contrast to the Schizoid, who inherently recoils from any social attention.

Why Do Personality Disorders Co-Occur?

Essentially, troubled backgrounds that are conducive to one PDO are often conducive to another and revolve around theme(s) that complement one another. Consider the following two inter-cluster examples:

- Antisocial and Paranoid PDOs often evolve from early histories where suspiciousness of others in their environment and looking out for number one is essential to survival. Unfortunately, as they emerge into the world and may even be away from the environment that engendered the suspiciousness and self-centeredness, the aforementioned relational approaches, the only ways they know how to interact with the world, have crystallized into a two-pronged, maladaptive interpersonal style.

- The Borderline and Avoidant PDOs both harbor incredible fears of rejection that are rooted in early interpersonal experiences with attachment figures. Perhaps a particular parent was in and out of their life, and when they were available, were harshly critical. The stage is set: "People I want to be close to will abandon me," (a core schema of the Borderline) and "People will reject/abandon me because I don't measure up" (core schema of the Avoidant).

If, perhaps, the attachment figure simply left and was never heard from again, chances are only the Borderline condition would've evolved; if it was just the harshly critical parent, only the Avoidant.

The Dynamics of an Inter-Cluster Experience

Continuing with the Borderline/Avoidant example, what will likely be first observed is the classic Avoidant presentation. This is a person who has a penchant for negative self-comparison to others. They would desperately like to socialize, but believe they can't possibly be acceptable. In a classic example of projection, they assume others will also only see their deficits, so why bother interacting when they'll just disappoint and probably make a fool of themselves?

Thus, the Avoidant lives a sheltered life, only really sharing themselves with those in a tight circle whom they are extra-sure are accepting of them. They rarely advance in life because they suppose that taking risks will likely just end in failure and be further evidence of their inadequacy.

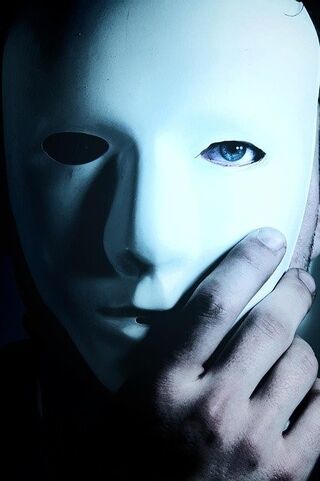

However, within this sheltered life, a mask periodically comes off, and it's obvious a parallel drama is playing out. People close to this person will likely notice they have little sense of identity, and there are spells of tumultuous, push-pull relationship dynamics. For example, if, after careful vetting, the Avoidant partners may exhibit a classic Borderline move of synchronizing to the partner's interests, fashion style, and/or religious beliefs. This not only generates some sense of identity, but, to our personality-disordered patient, is insurance against the partner rejecting them, for they see it as, "birds of a feather stay flocked together."

Eventually, the partner somehow does not live up to the patient's expectations, which the patient internalizes as a sign of pending rejection/abandonment. At this perception of rejection/abandonment, the Avoidant suddenly displays a defining Borderline reaction. They now seethe with anger and vilify their partner, impulsively, venomously, letting them know just what they think, and that they never should've bothered with them in the first place.

This preemptive death blow allows our patient to beat their partner to the finish line, and thus save face; i.e., "I pushed you away. You didn't abandon me, I abandoned you!"

Self-destructive activity ensues to distract our personality-disordered person from their emotional pain, perhaps even crescendoing in outright suicidal activity. True to Borderline form, this is also used as a tool; "Look what you've done to me!" This draws the partner back in to rescue them, for who wants to be responsible for someone's demise? The rescue attention received demonstrates to the personality-disordered individual that they are not being abandoned, thus completing the cycle by assuaging the major fear of both the Borderline and Avoidant.

Though the waters have calmed back to a baseline Avoidant presentation, in the background runs Borderline software, scanning for signs of abandonment, ever ready to warn of threats like a Malware popup, and spring to desperate, face-saving action.

Treatment Implications

Some researchers, such as Silva et al. (2018), have found that having a mixed PDO presentation is not necessarily an impediment to psychotherapeutic intervention. Regardless, once a therapist realizes more than one PDO is at play, they would do well to understand how the conditions complement/influence one another, as therapy may become more of a balancing act than usual.

In our example, for instance, it would be hard to address the Avoidant or the Borderline components in a vacuum. This is because they are symbiotically pathological, in that any social headway on the Avoidant front can be cut down by the Borderline behavior.

This leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy that people indeed don't find them acceptable, stoking the flames of "why bother?" and engendering a return to their ultra-sheltered life. Should they eventually continue to try and interact with someone in that tight circle whom they confronted, and they are held responsible, it may well engender another episode, and the cycle continues.

Disclaimer: Material provided in this post is for informational purposes only and not intended to diagnose, treat, or prevent any illness in readers. The information should not replace personalized care from your provider or formal supervision if you're a practitioner or student.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Vadym Pastukh/Shutterstock

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Grant, B., Stinson, F., Dawson, D., Chou, S., & Ruon, W. (2005). Co-ocurrence of DSM-IV personality disorders in the United States: Results from the epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46(1), 1-5.

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality (3rd ed). Wiley.

Silva, S., Donato, H., & Madeira, N. (2018). The outcomes of psychotherapy in mixed features personality disorders: A systematic review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry, 45(6). https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-60830000000180

Skewes, S., Samson, R., Simpson, S., & van Vreeswijk, M. (2015). Short-terms group schema therapy for mixed personality disorders: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01592/full

Turner, R.M., (1994). Borderline, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. In M. Hersen and R.T. Ammerman (Eds.), Handbook of Prescriptive Treatments for Adults (pp. 393-420). Springer.

Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., Boonyanaruthee, V., Pinyopornpanish, M., & Intaprasert, S. (2015). Comorbid personality disorders among patients with depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 1091-1096.