Around this time seven years ago, I was driving from Missouri, where I’d been covering the case of the police officer Darren Wilson, to Ohio, where my girlfriend’s (now wife’s) family was hosting Thanksgiving. It seems almost quaint now, given all that’s happened between Ferguson and a jury today convicting three white men of murdering Ahmaud Arbery, but at the time everything about the Wilson case felt like the height of scandal: the closed-door grand-jury deliberations and the smirking announcement by prosecuting attorney Robert McCulloch that the officer who killed Michael Brown would not face criminal charges.

A few days earlier, I’d watched Brown’s mother, Lezley McSpadden, wail in despair outside the Ferguson police station. A crowd of supporters, reporters, and protesters had gathered with her under the holiday lights, under the black sky, in the cold that had shocked me with its bitterness when I first landed. Riots and looting broke out. There was a Rite Aid that looked like a tank had rolled through it, with candy and Band-Aids half-submerged in the sprinkler water that covered the floor. I saw a stolen SUV burst through the door of an auto-repair bay and peel off into the smoke-filled night, its tires screeching as it reversed through the parking lot.

That night was the template, in many ways, for how such verdicts would be received in the years to come. Race was the topic on everyone’s lips for the first time in what felt like years. To people in Wilson’s camp, to bring up race was a smear that distracted from the case’s uncontroversial essence: that when a person fights a cop, the cop has the right to kill them. To others, the interaction’s context was proof to the contrary. Brown was killed in a mostly Black city with a mostly white police force that treated residents like cash machines for the government, harassing and saddling them with obscene numbers of tickets and amounts of legal fees.

Inside the Clayton County courthouse where McCulloch presented his case to the grand jury, the terms of the dispute were more visceral. “It looks like a demon,” Wilson testified, comparing Brown, a teenager, to a lead-resistant Hulk Hogan, “that’s how angry he looked.”

If many Americans, in the years that followed, have internalized the notion that invoking race is primarily a cudgel for the left, a way to gain moral high ground and partisan advantage by trading good-faith debate for broad accusations of racism against conservatives, Wilson never lost sight of the potency of a Black monster. “It looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots, like it was making him mad that I’m shooting at him,” the officer continued, characterizing Brown’s behavior as he filled him with bullets. “And that face that he had was looking straight through me, like I wasn’t even there, I wasn’t even anything in his way.”

Wilson’s vivid explanation worked to his advantage. He was exonerated not just then but also later. Wesley Bell, the Black St. Louis County prosecuting attorney who ousted McCulloch in 2018, reviewed the case and chose not to prosecute.

So the fact that we’re here again, at the end of another case where a Black man was shot dead by a frightened white man, is less notable for its sense of déjà vu than for being a reminder of who the invocation of race is usually meant to help. According to reports, it wasn’t until their closing arguments in the Arbery case that prosecutors brought up race at all. On February 23, 2020, Gregory and Travis McMichael and William Bryan Jr. — a white father-son duo and their neighbor — chased Arbery, an unarmed Black man, through Satilla Shores, Georgia, before Travis McMichael confronted and killed him. “Mr. Arbery was under attack,” said Linda Dunikoski, Cobb County’s senior assistant district attorney, because he “was a Black man running down the street.”

This was a departure from what analysts have described, alternately, as a baffling omission they’re “at a loss” to explain, and a prudent strategy to avoid losing the trial by offending a jury that was nearly all white (or to avoid getting a guilty verdict overturned, because an appellate court might find the inclusion of race to be “prejudicial”). “If prosecutors felt that they were winning … they might have decided the risk”—of making race a more salient topic—“was not worth it,” the New York Times wrote, summarizing the analysis of University of Georgia law professor Ronald L. Carlson.

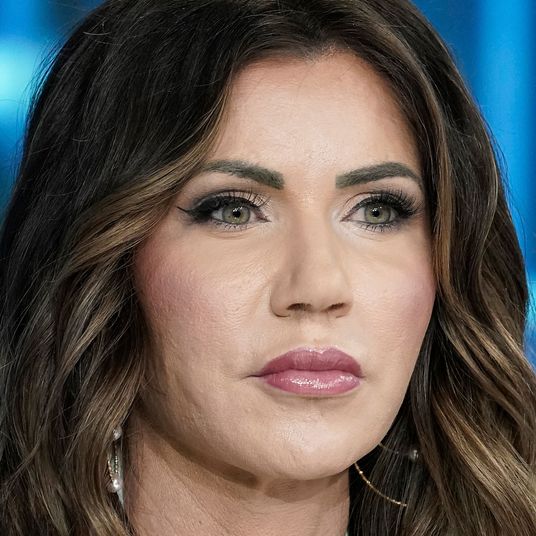

The defense team had few such qualms. Whether explicitly or obliquely, attorneys for the accused brought up race several times, both to delegitimize the social-justice movement outside the halls of the trial and to play up the alleged threat that Arbery posed to neighborhood security. Laura Hogue, the defense attorney for Gregory McMichael, described Arbery as a sinister figure who lurked inside “a home drenched in absolute darkness,” with no socks and long, dirty toenails. Arbery was one of several people who were seen, over the course of several months, on surveillance footage entering a partially built home in the neighborhood. The home’s owner gave conflicting accounts about whether anything had been stolen, but the trespassers’ presumably nefarious intent inspired McMichael’s pursuit.

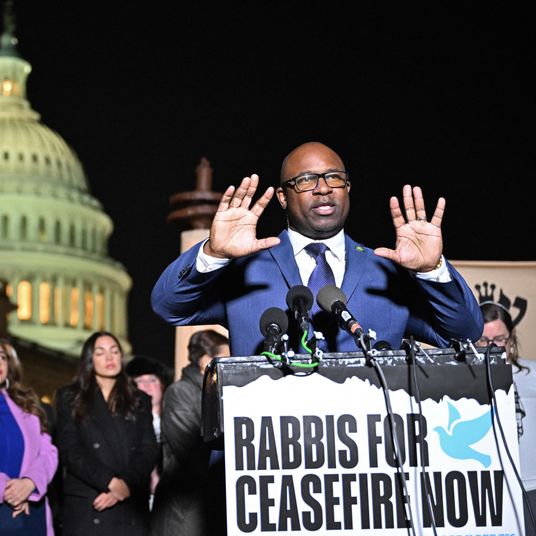

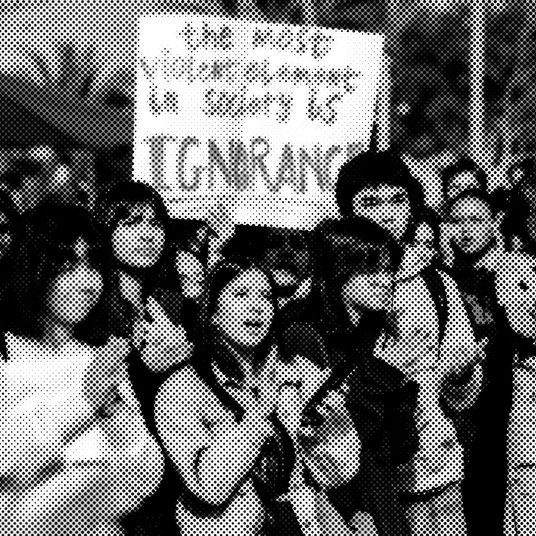

Kevin Gough, the defense attorney for William Bryan Jr., was more blunt. “We don’t want any more Black pastors coming in here or other Jesse Jackson, whoever was in here earlier this week, sitting with the victim’s family trying to influence a jury in this case,” he said to the judge last Thursday, when the jury was out of the courtroom. The next day, after his remarks inspired a protest led by Al Sharpton outside the courthouse, Gough filed a motion for a mistrial, claiming the crowd was a “woke left mob” set on “a public lynching in the 21st century.”

These different approaches were calculated with several concerns in mind, legal and otherwise. The defense might have felt a need to distract from their clients’ predilections. Travis McMichael, the man who shot Arbery, had a vanity license plate on his truck of the former Georgia state flag, which prominently features a Confederate battle emblem, and allegedly used a racial slur after killing Arbery. His father, Gregory, equated the Black man to a “rat” they’d “trapped,” and Bryan cited “instinct” as the reason he felt Arbery was guilty of a crime. Several of the defense lawyers concluded that the better bet was taking what looked like strong indicators of racial animus among their clients and recasting them as more reasonable concerns about leftist overreach and suburban safety.

The verdict on Wednesday revealed that the gambit didn’t work, but it remains true that the law is never applied based on objective interpretation. Sometimes you just have to calculate the odds and hope it works out. On my trip from Ferguson to Ohio in 2014, I was pulled over by state police just after crossing the Illinois border. The cop was white and young — probably a couple of years younger than my 27 — and his voice shook when he explained that he had pulled me over for speeding. I’d like to be generous and say he was rattled because the town over the border was dotted with charred ruins, and every interaction between a Black civilian and a white cop felt especially fraught, and he wanted to get this one right. But it could’ve just as easily been that I scared him. That would’ve been a legal reason for him to kill me and attribute his actions to some furtive or sudden movement I may or may not have made.

If you’re putting together the defense strategy for the off chance that this encounter ends up going south, you have to choose whether to play up what makes his alleged fear most vivid for an American jury. You look at my dead body, which is Black, consider how this sort of thing usually unfolds, and realize it’s not much of a question. You play the numbers.