A living descendant of the famed Lakota leader Sitting Bull has been confirmed using a novel technique for analyzing fragments of the historic figure's DNA.

Scientists were able to trace family lineages from ancient DNA to verify that 73-year-old Ernie LaPointe of South Dakota is Sitting Bull's great-grandson and closest living descendant. The findings, published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, will likely help LaPointe in his long-standing fight to move the Lakota leader's remains from their current burial site in Mobridge, South Dakota, to a location he said has more cultural relevance to his great-grandfather.

Eske Willerslev, a professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Cambridge, said his research normally focuses on piecing together ancient DNA to understand human genetic diversity and how different groups of people around the world are similar and distinct. But he couldn't pass up the opportunity to study Sitting Bull's DNA.

"I've always been extremely fascinated by Sitting Bull because in many ways he was the perfect leader — brave and clever, but also kind," said Willerslev, who is also director of the Centre of Excellence in GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen.

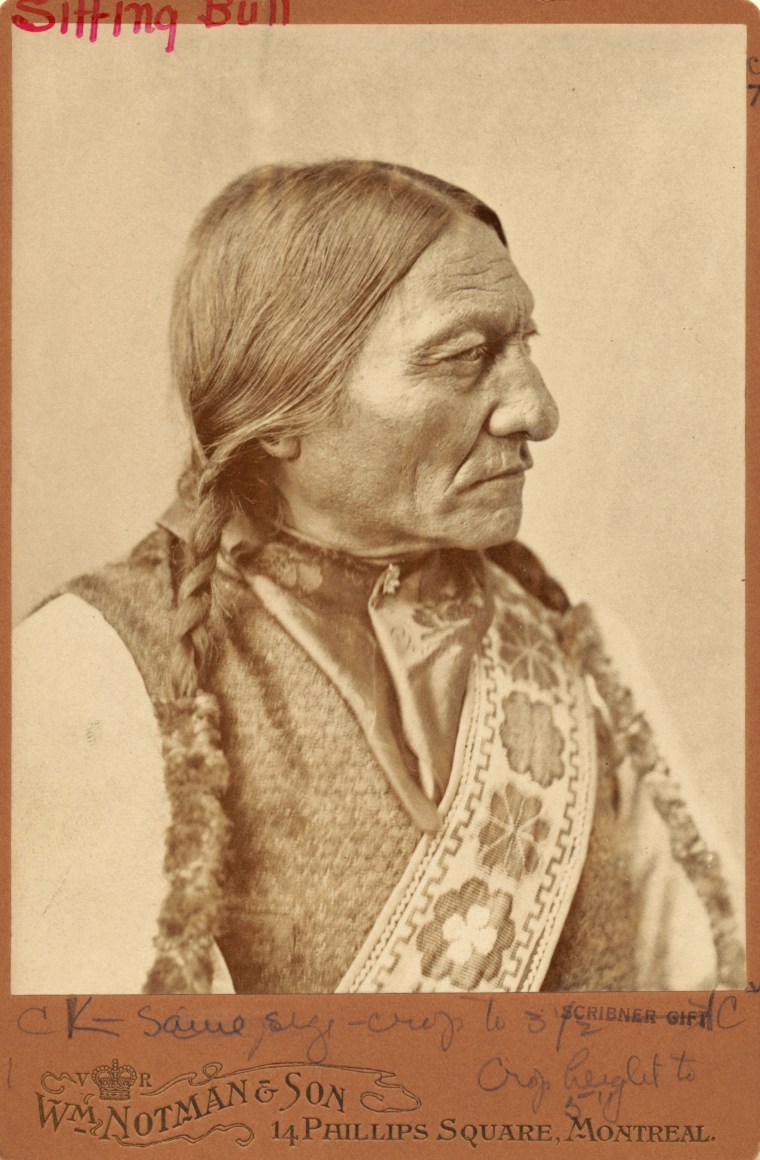

Sitting Bull, born in 1831, was chief and medicine man of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux. He united the Sioux tribes across the Great Plains in the late 19th century and led the resistance against settlers who were invading tribal lands. After he was killed by Native American police in 1890, an Army doctor at the Fort Yates military base in North Dakota took a lock of Sitting Bull’s hair and his wool leggings.

The hair and and leggings were obtained by the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., in 1896, but both items were repatriated to LaPointe and his family more than 10 years ago.

When Willerslev heard more than a decade ago about LaPointe's efforts to claim the Lakota leader's bones for reburial, Willerslev said he felt compelled to assist.

"I reached out because I'm an ancient DNA researcher," he said. "I told LaPointe, 'If you want to do this, I think I can help you.'"

Obtaining enough usable fragments of Sitting Bull's DNA from the small hair sample proved challenging. Willerslev said the hair had badly degraded after being stored at room temperature at the National Museum of Natural History for more than a century.

"There was very little DNA in the hair — way too little for established methods of DNA analysis," he said. "So we had to develop a new method."

It took the scientists 14 years to develop a technique to search for "autosomal DNA," which is non-sex-specific DNA that people inherit from both their mother and father.

The researchers compared autosomal DNA from Sitting Bull's hair sample to DNA samples from LaPointe and other Lakota Sioux to establish the familial connection.

Typically, genealogy studies focus on sex-specific genetic matches, such as zeroing in on the Y chromosome, which is passed down to male descendants, or specific DNA in the mitochondria that is passed from mothers to their offspring. But since LaPointe claimed to be related to Sitting Bull on his mother's side, Willerslev said his team could not rely on these more traditional methods.

Kim TallBear, an associate professor in the faculty of Native studies at the University of Alberta, said that while confirming Sitting Bull's family lineage may help LaPointe win the dispute over his great-grandfather's final resting place, the study's findings likely don't represent an "aha" moment for the Lakota and other tribal communities.

"To my knowledge, there’s never been any real challenge to Ernie LaPointe and his siblings' direct descent from Sitting Bull," TallBear, who is a member of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, said. "We have detailed genealogies that we keep through oral history and now also tribal genealogical documentation."

She added that these types of studies are complicated because they risk further exploiting Indigenous communities.

"Any time we participate with a scientist in reaffirming genetic definitions of what it means to be Indigenous, we are de facto helping to uphold their definitions over our own," TallBear said. "But we're stuck between a rock and a hard place because settler institutions control the disposition of Sitting Bull's remains."

Willerslev said the new method of DNA analysis could be used to confirm other familial relationships between living and historic people or to assist forensic investigations where DNA evidence may be scarce.

It’s also possible to use autosomal DNA for other high-profile genealogical studies, he added.

“In principle, you could investigate whoever you want — from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian tsar’s family, the Romanovs,” Willerslev said in a statement. “If there is access to old DNA — typically extracted from bones, hair or teeth — they can be examined in the same way.”