When I set out to chronicle a book-of-record on the 49-year history of HBO, I was met with a multitude of choices to make — especially when searching for a “spine” to hold it all together.

Will it be technology? HBO utilized satellite transmission before either ESPN or the Turner networks did. Perhaps the disruptive and transformational work HBO did in documentaries, or maybe movies — either producing its own spectacles or having a major impact on the financing of others. Or sports: HBO lifted boxing off the canvas and let it live once more, long after it was pronounced dead. What about the very notion of being the first successful pay television network? Or, most obvious, original series programming, which revitalized episodic shows that had been widely considered stale, even moribund.

Beyond all that, is there a single image, figure, or frontage that can instantly symbolize HBO to the world? Of the many contenders for top trope, one surely emerges: the fascinating, cherubic, contrarian image of James Gandolfini, dominating and irresistible star of HBO’s crown jewel, The Sopranos.

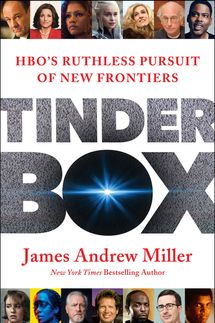

Below are two excerpts from my new book Tinderbox: HBO’s Ruthless Pursuit of New Frontiers. The first chronicles the cultural impact of The Sopranos and the ways in which the series catapulted a relatively little-known character actor to a level of celebrity few reach. Following that is a section from later in the book that recounts, in the words of Gandolfini’s collaborators, how the late star grappled with his fame.

Excerpt from 'Tinderbox: HBO's Ruthless Pursuit of New Frontiers'

Although Chris Albrecht owned a beautiful Mediterranean-style house in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles, for his East Coast sojourns HBO rented its CEO a showpiece apartment in midtown Manhattan’s Museum Towers, not far from Radio City Music Hall. In the late spring of 2003, Albrecht played host there to more than a dozen invited friends and associates for an urgent meeting, one that concerned the pay network’s most important show, and one of the most celebrated dramas ever — The Sopranos. Then in its fourth season, The Sopranos was proving immensely popular with audiences and was in the process of becoming as much a watershed for television as Citizen Kane had been for motion pictures.

And yet the show that had come shockingly close to never existing in the first place was, at that moment, on the cusp of collapse.

David Chase, auteur of the series, had originally written the pilot script for the Fox television network, but after a short flirtation Fox executives passed on the project, condemning it to turnaround, that limbo from which many a series or film has failed to return. HBO came onboard shortly thereafter, however, and produced a pilot. After it was shot and edited, the pilot was test-marketed in several cities, to a tepid response. Networks confronting such a meager reaction would likely have passed on the pilot then and there. At HBO, where things were done differently, Albrecht and colleague Carolyn Strauss — fully supported by HBO CEO Jeff Bewkes — decided to go with their guts rather than succumb to the research. The Sopranos was ordered to series.

At this point, the show’s leading man, James Gandolfini, was a little-known character actor who tended to disappear artfully into his roles — some of them, appropriate to his size, “heavies.” Whether he was playing a ruthless mob henchman in True Romance or a bearded southern stuntman in Get Shorty, his work had not been wildly auspicious or lavishly praised by critics. Nevertheless, Chase — who had earlier considered actor Michael Rispoli and musician Steven Van Zandt for the lead role (both men would end up in the series as Jackie Aprile and Silvio Dante, respectively) — personally picked Gandolfini as his guy because he passed the “real world” test. Simply put, he looked the part. Casting Gandolfini turned out to be a stroke of brilliance. When, on January 10, 1999, The Sopranos premiered with Gandolfini, then 38, in the plum role of Tony, the Soprano paterfamilias, the actor would soon find himself aglow in the brightest spotlight of his career. The series didn’t start with that big a bang commercially, but then, in episode five of that first season — when Tony strangled and sent an old nemesis to hell while touring potential colleges with his teenage daughter, Meadow — something on the show clicked confidently into place. Gandolfini’s life would never be the same and, arguably, neither would television.

The Sopranos — for anyone who was in a coma or visiting other planets at the time — is a drama about the double life of Anthony “Tony” Soprano, husband and father to an upper-middle-class family in suburban New Jersey and, simultaneously, capo di tutti i capi to another sort of family, organized- crime division. For both Tonys, the times they were a-changin’; a series of panic attacks rattles his world, compelling him to secretly consult a psychiatrist, brilliantly played by Lorraine Bracco. They have lots to talk about, including the fact that Tony’s Machiavellian mother and his sinister Uncle Junior figure prominently in the crime family’s operations. Real-life realities would impose themselves on the narrative; Nancy Marchand, the veteran character actress cast as Tony’s mother who served as one of the show’s most essential arteries, became very, very sick, and ultimately died, at the end of season two. But by that time Chase, who ran the show tirelessly, had been hard at work creating countless new dimensions to his magnum opus, expanding it to a much larger scale than previously envisioned. The New York Times would call The Sopranos “the greatest work of American popular culture of the last quarter century.”

As a result, even more weight was placed on Tony’s, and Gandolfini’s, shoulders.

To say that Gandolfini rose to the occasion would be putting it mildly. His complex, nuanced, and inspired performance demonstrated remarkable range, not just over the course of the series, or any one episode, but often within a scene, a confrontation, even a single moment, that seemed to transcend mere “acting.” No matter how despicable Tony’s behavior appeared on the surface, Gandolfini was so persuasive and affecting —whether conveying Tony’s rage, passion, or some fleeting flash of guilt — that the audience never turned its back on him. In a troubling age of anti-heroes, Tony Soprano was royalty. His eyes told a million tales, and his performance elevated him to the upper echelon of American actors. He adapted handily to the series’ widened scope, its growth from intimate portrait to rich, blood-splattered tapestry, and he was enormously instrumental in making The Sopranos an epochal cultural event — unofficially the start of what some would call television’s “second golden age.” Whether that’s true or not, it was a golden age of Gandolfini.

“Jimmy,” to his friends, wasn’t just the lead actor in a cast of character

actors — adroit professionals all — but was also the leader of the surrogate family that evolved offscreen. Gandolfini set the tone, not by asserting star clout on the set but because his fellow actors shared great respect and admiration for him as both artist and friend. He returned their affection with a sincerity that embraced deeds as well as words, typically declining interview requests from the press until reassured that another cast member would be included to share the limelight. Gandolfini was so patient with clamoring fans that he didn’t even balk when one of them asked to shake his hand as he stood at a men’s room urinal.

Gandolfini’s worldview soon exceeded the boundaries of show business. He became, for instance, deeply involved in the plight of battle-scarred veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan, even to the point of later producing a documentary about their struggles, conducting many of the interviews himself. When playing Tony, though, Gandolfini underwent an awe-inspiring facial and bodily transformation; the lovable pussycat turned into a ruthless and philandering gangster. Somehow it seemed beyond acting, beyond even intuitive skills; Jimmy became Tony, an actor of unimpeachable credibility.

There’s no way of knowing if The Sopranos would have been the sensation it became if some other actor had been cast in the role that Gandolfini made so irrevocably his, but chances are that magical alchemy would not have happened. He elevated his fellow actors, as well as every script, and was incalculably instrumental in making The Sopranos an international phenomenon. People didn’t just admire Gandolfini; they were drawn to him, and the character he played, passionately.

For all his brilliance in the central role, however, the road to glory for Gandolfini and The Sopranos would be cratered with potholes. There were, for instance, fitful bouts of disruptive incredulousness as he reacted to cer- tain scripts he was handed. Gandolfini, who once remarked that after a day of shooting, he often had to take a shower because he felt “dirty” playing the role, would sometimes balk at a particular scene and instead of asking Chase, “Do I have to do this?” he would wonder out loud, “What the fuck is this?” and then declare flatly, “I’m not doing it.”

Gandolfini’s longest and strongest tantrum erupted over a script that called for Tony to dash into a gas-station bathroom and masturbate during a period when Tony was having an affair with feisty Realtor Julianna Skiff, played forcefully by Julianna Margulies. But even that time, despite his earlier protests, Gandolfini relented and played the scene as written. As it turned out, the gas-station sequence was shot but then edited out of the finished episode. To his credit, Gandolfini never complained to Chase that the difficult scene ended up on the cutting-room floor.

Gandolfini and his team would prove much more formidable when it came to business. They understood how indispensable he was to the series. They knew no one could replace him. So Gandolfini, at the urging of his representatives, staged a notorious holdout during particularly prickly contract negotiations. Gandolfini’s contract wasn’t even up, but HBO had agreed to open up discussions in 2003 to give him a new deal, a concession it didn’t legally have to make. What began as a stubborn standoff between star and network grew increasingly nasty, so much so that at one point during negotiations, an angered Albrecht called Gandolfini a “fat slob,” an outburst that he later regretted, especially since he’d been one of Gandolfini’s most devout champions from the beginning. Indeed, the show and its star would never have made it through the HBO chain of command if not for Albrecht’s essential and passionate advocacy. As for the big blowup over contract terms, the two sides found a way through the impasse after three months, and Gandolfini was back in action.

A long-running television series can be hard on everybody involved. Cast, crew, and network executives get tossed together in a pressure cooker for years on end, and it’s rare that some don’t suffer accordingly. The very success that many dream about can become a gilded cage; confinement on a show — even one like The Sopranos, with its long, built-in hiatuses between seasons — can’t necessarily exorcise agitated personal demons.

It wasn’t just a matter of coming up with quality scripts and continuing to make talked-about episodes, although that’s hardly child’s play, by any means. Even with new contract terms in place, Gandolfini and the show weren’t out of the woods. One of the reasons Gandolfini had been able to hold such a tough line during contract negotiations is that a part of him had realized a horrible secret: Tony Soprano’s struggles onscreen not only often mirrored his own but at times amplified them. So there was a part of Gandolfini that wanted to leave the show because he understood, as he told a friend, that in order to “become” Tony, he had to connect with his darkest side. In essence, the cost of him playing Tony went beyond just being an actor. He lamented several times, “You don’t understand what this is doing to me.”

The more audiences watched and praised Gandolfini as Tony, the more his personal journey became problematic. Jimmy had suffered from alcohol and drug abuse — those twin consoling companions of both success and failure— for years, and the stress of occupying the lead role in a smash hit was formidable. Of his substance abuse, Gandolfini said: “When I was 20 or 18, it started … and it progressed through the years.” In 1997, he was arrested for DUI and adopted antics befitting a living legend, which at the time he had yet to become.

Fame rarely, if ever, makes past struggles disappear. Since The Sopranos’ premiere, dark murmurs had circulated regarding Gandolfini’s behavior, tales that admittedly started out more amusing than alarming — such as when, at a glittery Golden Globes affair, upon hearing Time Warner chairman Jeff Bewkes griping that “this wine is shitty,” Gandolfini grandly reached under HBO’s table and produced three bottles of Brunello that he’d just happened to bring along. It was hardly scandalous comportment, but it did qualify as quixotic and thus in character — not Jimmy being Tony but just Jimmy being Jimmy.

Many more, and considerably worse, stories were to come.

There followed a spate of awkward MIA situations — Gandolfini arriving late for a shoot or failing to show up altogether. One day filming was halted while a search party looked high and low for their star, eventually locating him in a Brooklyn nail salon. In the wake of such episodes, Gandolfini appeared at times embarrassed to be around those who knew of his “issues,” and, ever the good soul, would express his contrition by spreading gifts among all those affected. Nevertheless, Gandolfini misdemeanors mounted. There were several more disruptive disappearances that resulted in halted production, costing HBO several million dollars. Executives at HBO and Time Warner, HBO’s corporate parent, initially believed the best policy was that, no matter what, the Great Gandolfini was not to be issued ultimatums or otherwise threatened. As one executive noted, the object was always to be “helpful, not punitive.” Accordingly, the errant actor was gently reminded that he was a member of the great HBO “family” and that his ongoing issues would be dealt with in that spirit.

The approach failed. Gandolfini had been announced as a star presenter for the Golden Globes telecast in 2005 but was missing when the curtain was about to go up. Word circulated among the tightly knit group that Jimmy was MIA again. Minutes later, Gandolfini was located lying on the ground outside the Beverly Hilton where the ceremony took place, making snow angels on the lawn, so inebriated that he didn’t seem to notice the absence of snow. Clearly, a Golden Globes plan B needed to be hurled into action. Michael Imperioli, who co-starred in The Sopranos as headstrong Christopher Moltisanti, was quietly approached to take over presenting chores for Gandolfini, but he was hesitant to attempt filling the big guy’s shoes. Besides, a worldwide audience was expecting Gandolfini. When it became clear there was no practical alternative, Imperioli relented and exe- cuted his role deftly, later telling Gandolfini that he thought he, Michael, deserved the $25,000 “goody bag” of gifts that presenters received from the sponsoring Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Gandolfini was more than glad to hand it over.

It was the type of situation close friends, family, and key individuals involved in The Sopranos had hoped to avoid when they gathered in Albrecht’s elegant Manhattan apartment that night in May 2003. Most shared the belief that the intervention they were about to attempt was not just advisable but a matter of life and death — Gandolfini’s and that of the entire series.

When Gandolfini entered Museum Towers, he was still under the impression that he and Albrecht were having a casual get-together, little suspecting he’d be confronted by an intervention committee of about a dozen — among them, David Chase and several friends and family members. Nor did Jimmy know that a private plane was standing by to take him directly to rehab. There had even been two days of intervention “rehearsals” testing myriad scenarios and trying to anticipate Gandolfini’s possible maneuvers.

As it turned out, none of that preparation proved helpful. The entire intervention lasted ten seconds. Gandolfini walked into the apartment, saw everyone, sized up the situation in a snap, and immediately barked, “Oh, fuck this. Fuck all of you.” Glowering at Albrecht, Gandolfini dared him with “Fire me,” then stormed out. While the others sat stunned, one of Gan- dolfini’s sisters chased her brother down the hall and begged him to come back.

But Jimmy was having none of that.

Gandolfini was loved and cherished. Throughout 757 interviews conducted for Tinderbox, his name came up more than any other, and eight years after Gandolfini’s death, the pain of that loss is still raw.

EDIE FALCO, Actor:

Several years ago I went to the play God of Carnage that Jim did with Marcia Gay Harden, and when they walked in together onstage and sat down next to each other as a couple, I had a totally unexpected wave of jealousy come over me. I thought, “What the hell is this bizarre thing?” I wasn’t expecting such a reaction, it snuck up on me, but there was a little crossover there. I quickly corrected my mechanism, and everything was fine. But it’s compli- cated. It’s mind games.

A big part of therapy and all these journeys I’ve been on has been learning to separate my life and my work. If I was supposed to be in love with another character, I thought it was part and parcel of really losing myself in that character, and the two lives blending, real life and fake life. I got myself in some very, very dangerous, complicated, and unpleasant situations as a result. I could lose myself when they were bleeding into each other. Now I’ve learned to explore with boundaries, without fear of disappearing, and still feel safe.

SHEILA NEVINS, Executive:

We went to Walter Reed together for Alive Day Memories. Jim was the big, big, big celebrity. Everybody was starstruck. We went through these rooms with terribly injured soldiers. It was all very difficult, but Jim was great with everyone. He signed people’s casts. Everybody knew the show; no one referred to him as Jim; they all referred to him as Tony.

In this one room, there was a woman sitting by a bed of a heavily bandaged young man. The woman said, “Oh, my son loves you.” She closed her Bible, and she said, “He’s in a coma, but please talk to him. Maybe you can help him get better.” Jim starts talking to him, like Jim. He says, “You fought for our country, you’re a great guy, and I’m very proud of you.”

She said, “No, not that voice, your real voice.” He knew what she meant and started talking to him like Tony. He instantly changes into Tony Soprano and says, “You got to get out of this bed, and show your mother a thing or two. Just because you went over there and fought for your country doesn’t mean you can make your mother cry.”

Then she asks him to sign her Bible. He signs it “Jim Gandolfini.” She says, “No, not him. Not him.” Now he signs it “Tony Soprano.” He’s willing to do anything for this kid and his mom. We walk out of the room, and he rushes ahead of me through a door marked laundry room. When I get there, he’s got his head buried in folded laundry, and he’s sobbing like a baby.

MICHAEL IMPERIOLI, Actor:

We went to some dark places as characters on the show, very emotional places. We trusted each other and had each other’s backs. We also had a lot of fun, a lot of laughs. I acted with Jim more than I’ve acted with any other actor in my career, probably more than I ever will with another actor. And for that, I’m really grateful.

TONY KUSHNER, Writer:

At the end of Emmy night 2004, around 2 a.m., Mark [Harris] and I went back to our hotel where Gandolfini was standing in front, along with some other people from the cast. He said, “We’re going out for a hamburger. Do you want to join us?” I was too intimidated and felt awkward. I said, “I can’t, but thanks.” And I bitterly regret that because I adored him.

I had been on a plane with him — my dog rode under his seat — the year that Lincoln was made, and he was in Zero Dark Thirty. As soon as the plane landed, they announced the Oscar nominations. James grabbed my head and gave me a big kiss right on the mouth. I was in heaven.

In June 2013, Gandolfini brought Michael, his 13-year-old son, to Italy (where else?) to celebrate the young man’s graduation from junior high school. On the morning of the 19th, the two explored the Vatican, where a tourist snapped a photo of James as he visited the Egyptian Gallery and the Book of the Dead. That night, father and son ended the day with dinner at the hotel’s open-air Boscolo Exedra Roma. But a day of elation turned into a night of tragedy. Gandolfini collapsed in the bathroom of the suite and was discovered there by his son. A call for emergency service went out at 9 p.m., and less than eight minutes later, Gandolfini was being rushed to the hospital.

At 10:40 p.m. Italian time, James Joseph Gandolfini Jr. was pronounced dead.

MARA MIKIALIAN, Executive:

New York was already closed. Every single phone lit up in our L.A. office. Our colleague Angela Tarantino was one of the first to learn of Jim’s passing. She started working with Jim on The Sopranos and never stopped. She was also close with his family and on that night, as well as over the course of the next several days, her focus remained on them. So by default, I became very involved.

The entire situation was unprecedented. Somebody had tried to sneak into his hotel room that night, so we contacted a producer we worked with in Rome, who brought on a whole security team. When his body was being transferred to the airport, we used a dummy vehicle that went in a different direction than the actual one. There were so many rumors and concerns; everyone was relieved when the coffin made it safely on to the plane.

HBO confirmed Gandolfini’s death that evening with a statement: “We’re all in shock and feeling immeasurable sadness at the loss of a beloved member of our family. He was a special man, a great talent, but more importantly a gentle and loving person who treated everyone no matter their title or position with equal respect. He touched so many of us over the years with his humor, his warmth, and his humility. Our hearts go out to his wife and children during this terrible time. He will be deeply missed by all of us.”

That night, HBO aired the Sopranos episode titled “Where’s Johnny?” followed by the onscreen message: “HBO mourns the loss of James Gandolfini, a beloved member of the HBO family.”

Secretary of State John Kerry coordinated with the U.S. Embassy in Rome and Italian authorities to ensure Gandolfini’s repatriation was accomplished as quickly as possible.

A private jet returned James Gandolfini Stateside Sunday evening. The next day, New Jersey governor Chris Christie ordered all flags at state buildings to fly at half-staff in Gandolfini’s honor.

QUENTIN SCHAFFER, Executive:

Jim’s funeral at St. John the Divine in New York City was like a scene right out of The Sopranos or The Godfather. Two thousand people gathered to mourn. The PR department was in mourning, too. We had all loved Jim, particularly Angela [Tarantino], so it was far from easy, but we were deter- mined to handle all the logistics, from invitations to ground transportation to staffing.

JON ALPERT, Documentarian:

I was waiting by the hearse’s door for the casket to come out, waiting and waiting. All of a sudden, I hear this swoosh, look up, and see an eagle flying in a big circle, then coming down to land on the church roof, right above the hearse. It just sat there and looked down on us. Then they bring the casket out, carry it into the hearse, and close the door. As the hearse drives away, the eagle flaps its huge wings and flies right over the back of the hearse, accompanying it out of the parking lot. After a few minutes, it then bolted into the sky. I’ve seen a lot of extraordinary moments, all over the world, and I’m not a very metaphysical or religious person, but there was something going on with the cosmos that day, and that eagle was there to tell me about it.

Adapted from TINDERBOX: HBO’s Ruthless Pursuit of New Frontiers, by James Andrew Miller. To be published by Henry Holt and Company November 16, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by James Andrew Miller. All rights reserved.