'Like a bowl of spaghetti': New map details intricacies of the brain

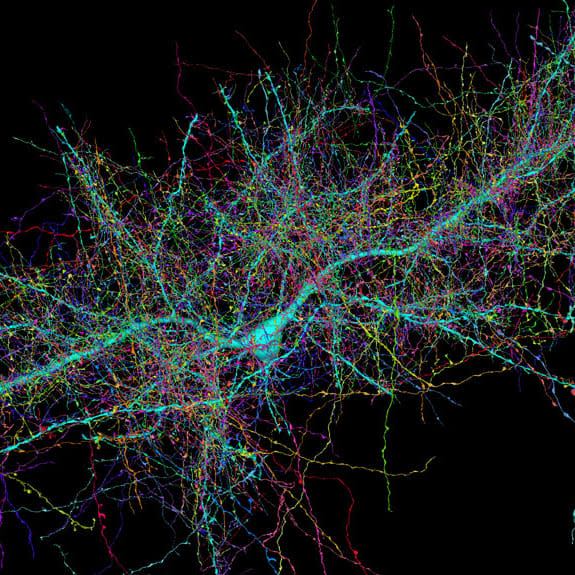

A map of a fragment of a human brain reveals for the first time its astonishing intricacy, while providing new evidence of both the brain's physical structure and one of the ways it's thought to function.

The map is the culmination of years of work by scientists to trace the vast network of cells and connections within the sample, which was taken roughly a decade ago from the brain of a patient undergoing surgery to prevent serious epileptic seizures.

Although the sample is just a tiny fraction of an inch across — about half the size of a sesame seed — it contains more than 50,000 brain cells, or neurons, and roughly 130 million of the thread-like axons that transmit signals between them. But it's only about a millionth of the volume of an entire human brain, which is estimated to consist of about 100 billion cells.

The interactive map can be explored in detail through the online Neuroglancer graphic interface, which was developed for the purpose of displaying complex images of brain tissue. It's now possible to see the different ways that the multitudes of neurons and axons of the human brain are connected by effectively making the tissues that surround them invisible and revealing the dense networks within.

"You can think of the brain like a bowl of spaghetti," said Dr. Jeff Lichtman, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, who headed the project. "We sliced it into very thin images and then traced each strand of pasta."

The Neuroglancer interface can be accessed and explored by anyone.

"When you get to look at things that you couldn't have seen before, it gives you an opportunity to start thinking about things in ways that go beyond your imagination," he said. "It provides us with views of a world that was alien to us … we're now beginning to see what it looks like."

The sample was taken from the temporal lobe of the patient's neocortex, an outer region of the brain's "gray matter" associated with hearing and memory. After it was surgically removed, he and his colleagues preserved it in a type of resin and stained it with heavy metals to reveal its cellular structure. They then used an automated diamond knife to cut the sample into more than 5,000 slices, each a thousand times thinner than a human hair, and made images of them with an electron microscope. The images were processed by artificial intelligence and "proofread" by human experts to map all the neurons and axons in 3D and in color — resulting in the largest dataset created for medical imaging, Lichtman said.

The yearslong project has yielded 1.4 petabytes of data — roughly 100 times greater than all of the information stored in the e Library of Congress, said Harvard neuroscientist Alex Shapson-Coe, a member of Lichtman's lab and the lead author of a new study on the project. Processing the data would have exceeded the combined computing power of Harvard University, and so the scientists turned to Google — one of the few organizations with enough computational capacity to help, he said.

The new views of the thinking part of the human brain have already provided fresh insights. One is that certain axons can connect to individual neurons more than a dozen times, while most connect only once. Lichtman speculates that these multiple connections could indicate memories or skills that have been "strengthened" by repeated use, such as learning to apply brakes at a red light, for example.

"If you are driving a car and you see a red light, you're not thinking that you have to lift up your foot, take it off the gas pedal, and put it on the brake," he said. "You're just doing it automatically."

The map has also revealed numerous "mirror neurons" within the brain, where two brain cells near each other point in opposite directions; and curious coiled bundles of axons. Neither structure has been seen before, but it's not yet known what they do, Shapson-Coe said.

He foresees that the new map could be used to reveal differences in the brains of people suffering mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, which are thought to be caused by variations in the brain's structure.

The new map comes as scientists grapple to learn how the human brain creates consciousness, in addition to its automatic functions such as controlling breathing and blood pressure.

"What is an idea? How does creativity work? We don't fully understand how learning works and the mechanisms of recall of memories are even more mysterious," said Seth Grant, a professor of molecular neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom.

Grant, who was not involved in the project, explained that the structure of the sample was probably representative of the brain's entire neocortex.

"It will be a useful reference resource for future studies that examine the differences between individual brains," he said in an email.

But it would not be enough just to know the "wiring diagram" of the brain revealed by its structure — scientists also had to understand the molecular composition of its myriad connections, which were now known to be of many different types, he said.