During the coronavirus pandemic, public discourse generally accepted the premise that disparate outcomes among racial groups were not due to any biological differences between those demographics. Discussions instead focused on the socioeconomic and political factors that fuel health inequality.

The same cannot be said for disparate COVID-19 outcomes between men and women. Overall, men are more likely to die should they contract COVID-19. Analysis of that fact has largely clung to assumed sex-related variables around genetics and hormones and how that could potentially affect the immune system.

The result, however, is the overlooking of one of the most adversely affected demographics: Black women, who, based on a new research paper from Harvard are more likely to die from COVID-19 than any other demographic except Black men.

Researchers Tamara Rushovich, a Ph.D. student in the Population Health Sciences Program at Harvard University, and Sarah Richardson, the director of Harvard’s GenderSci Lab, spoke with Slate about how their findings “could save lives.” This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s get started with an overview of the study.

Rushovich: We started back in the summer. There were reports showing the mortality and case rates among men and women, and we were beginning to see reports by race and some other variables, but generally in individual identity categories: the mortality rates among men, the mortality rates among women, and lots of things coming out about how men were dying at higher rates than women broadly.

We wanted to understand that a little bit more deeply, knowing that there are so many social factors for historical reasons related to racism, discrimination, history of economic deprivation, etc. that shape someone’s risk of exposure, access to testing, access to hospital resources, etc. If you look just at sex alone, you get one picture, but if you look across more axes, what does that look like and what does that mean for the sex disparity in COVID rates?

To get data to even look at mortality rates by more than one variable was initially hard to do because it was not available at the federal level. You could only see COVID rates either by sex or by race or by age, but not in a format where you could look at it across multiple variables. And we really wanted age because we know that COVID is different across age groups and older ages are at higher risks. We were able to get data from Michigan and Georgia, which were the only states publicly reporting data in that format. And that’s the basis of our study.

Our main findings centered around that, within racial groups, the sex disparity varies. The ratio between the rates among white men compared to white women is smaller than the ratio of the deaths among Black men compared to Black women. And the ratio within Asian men and women is comparable to the white men and women. When looking across, we saw that the disparity between Black women and white women is much larger than the disparity between white men and white women.

When you only look across one axis, you miss some of that variation and where are there actually quite high rates among particular groups that is not seen if you only look at race groups or at sex groups or age groups.

Richardson: That is an incredible finding that the disparity among women of different racial groups is larger than the disparity between white men and white women. The suggestion is that the disparity we really need to be looking at is that race by sex intersection, going back to the framework of intersectionality and structural gendered racism, as a key driver of outcomes in this pandemic. And the point that the disparity between Black women and Black men is larger than the disparity between white men and white women also tells us something about how those disparities are working within each group racially defined.

How much larger is the disparity between Black women and white women?

Richardson: It’s over three times the disparity between white men and white women.

Rushovich: The headlines have been “Men Fare Worse Than Women.” But who disappears in that picture? Black women who are dying of COVID at extremely high rates. That specific vulnerability is lost. It’s the Kimberle Crenshaw intersectionality story.

It’s very true that Black women end up missing in the narrative when we look at the data one way or the other. What does this data say about the way racism functions in America?

Rushovich: It’s showing that racism intersects with discrimination along gender and sex lines to become amplified, or work together, to both affect Black women and amplify sex disparities between Black men and Black women in a way that is reduced between white men and white women.

[Some of our hypotheses for why this might be the case] are things like occupation, where you see both racial and gender discrimination in terms of who’s performing what types of occupations and which of those are essential workers. There is an overrepresentation of Black women in home health aide and nursing positions, which are high exposure routes for COVID. There’s also the effects that structural and gendered racism has on comorbidities in terms of shaping the many different avenues that influence health.

Richardson: It’s well known that this exact pattern is what you would find if, for example, you looked in Georgia at heart disease rates by race and by sex. You would find Black men at the top and Black women after that. And a disparity among white men and white women that is less of a disparity and the rates overall are lower in those two groups. What that tells us is, like my colleague Evelynn Hammonds always says, COVID-19 did not create race disparities. It makes them visible.

And what we have observed in the discourse around sex differences is a focus, a rush to biological causal variables. But our research has shown that there are extreme variations in the degree of the sex disparity similarly across states.

All of this shows that biology would be a very poor candidate to explain these kinds of variations, just like we consider biology a very poor candidate to explain the extreme racial disparities that have been seen. Instead, they pattern along these well known social trajectories.

Why is it important to see that this disparity is due to structured gendered racism?

Rushovich: Where you see the cause coming from is where you then look to make the changes to fix it. If you see the cause, like Sarah was saying, in biological or genetic areas, then you’re going to lean towards medical and other kinds of treatment. But if you see it more coming from social and gendered structural racism as a cause, then you really have to look at institutional policy and social factors as needing to change to address the disparity.

Richardson: A ton of research and resources have gone into investigating these hormonal and genetic variables in the sex disparity. But Black feminist health scholars have been calling since the beginning of the pandemic for attention to structural gendered factors, such as the greater exposure of women of color in essential worker positions, special attention to protection from evictions—which overwhelmingly affect women of color and Black women.

Our findings support a much more cautious approach to making claims of sex disparities without considering interacting factors, because then you obscure those extreme vulnerabilities. If you only look at the claims about sex disparities, you would think the group to target is just men. And as our figures very clearly show, there are differential vulnerabilities within the group of men and within the group of women.

The study uses data from the two states. Does this limit the findings of the study or does it give credence to the qualitative information that’s already out there about how Black women are being disproportionately affected by COVID?

Rushovich: Michigan and Georgia are quite different and quite large states. Each state has done their own thing in terms of lockdowns, mask mandates, and policies. Those will likely influence the gender or the sex disparity because of the way it influences who’s exposed and who gets tested. I don’t think you can generalize, but the trends are something that should be looked at in other states. And I would expect we would probably see them in other states, but the degree can vary, because the response has been so different.

Richardson: Yeah, it is a limitation. We’d like to do 50 states. And as soon as we can, we will be doing more states. One of the other limitations is that most states don’t report data for Hispanics in a similar format, and that’s also a very high vulnerability group. Other analyses would include a greater number of race/ethnicity classifications and add sophistication to what we’re able to see. It wouldn’t change the degree of the disparity between Black people and white people that we see here, but it would add nuance in terms of other forms of vulnerability.

So it is a limitation, but as we have seen, each state in essence had its own pandemic. And so in a way, crunching all the data together is inappropriate and you do need to look state by state. It’s remarkable that we see such similar patterns between these two states, and it suggests that this is a real-deal patterning of structural gender racial disparities.

We’ve talked a lot about the social factors that likely cause such outcomes, but what could clinicians and policymakers do going forward to address these disparities?

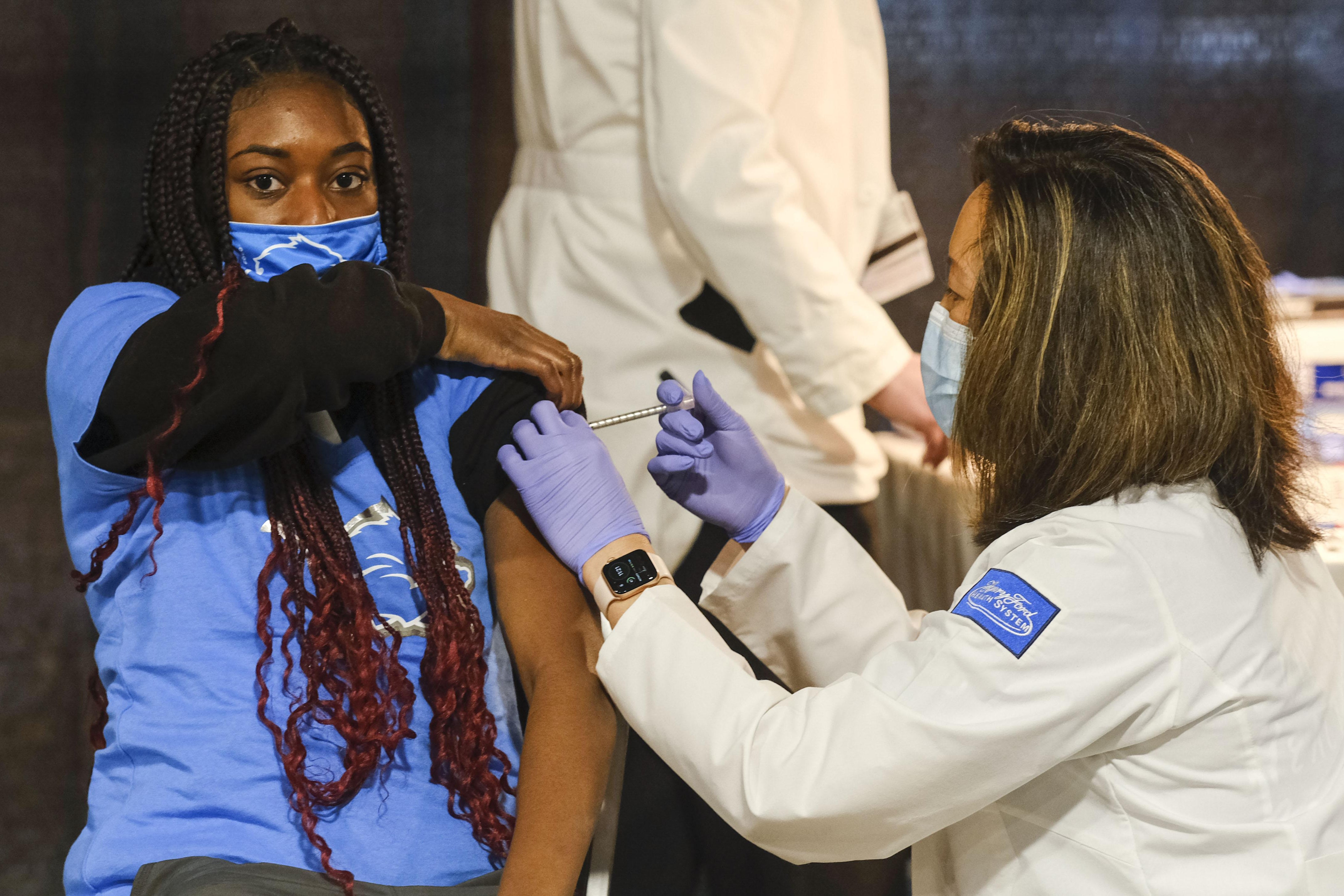

Rushovich: When we’re thinking about COVID relief bills going forward, looking at occupations that have people who are particularly affected by COVID—such as home healthcare workers and especially considering documentation status—and making sure those people are included in COVID relief legislation. Addressing evictions because you can’t shelter in place or stay at home when you’re evicted. And addressing the long legacy of structural gendered racism in the healthcare system in terms of bias and access to treatment and vaccines.

Richardson: In the clinical setting, a problem with the sex disparities claims is that when somebody comes in, they get seen as a man and thus vulnerable in some way, or as a woman and thus vulnerable in a different way. A fear at the clinical level of reinforcing this highly binary disaggregated way of thinking about vulnerabilities is that you get sex stereotyping in these environments that would lead to different trajectories for treatment, as some biological scientists have actually argued. And so we’ve been working hard to texture those kinds of assertions and stereotypes by highlighting the social dimensions of particular vulnerabilities.

A third area of recommendation is data reporting. This data actually is collected. It is just simply not reported in such a way that we can see for a single individual their age, their race, and their gender or sex, so that we can look at these patterns. It’s not made available in any accessible format. So if we could draw out more responsible, accountable reporting in a way that could allow us to see these patterns, that would be very high impact.

Rushovich: Then another point on the reporting which we’ve written a little about is the wide variety in the way that gender or sex is reported and whether it’s in a binary category, whether there’s an unknown, or a transgender, or a non-binary category. That also goes into the way that data are collected and reported.

Richardson: We really need better reporting of what is meant by sex and gender. Up to 5 percent of the population may identify as non binary or gender non-conforming or transgender. And currently this is absolutely not represented in the data reporting practices, and we have more stuff forthcoming on that.