Carolyn Eberly still has an urgent task on her mind a week before Election Day: finding the people who have yet to respond to calls or messages about their plans to vote.

“People have been calling and texting and writing and everything they can do and have not heard from these voters,” Eberly said, holding her clipboard as she delivered marching orders to fellow volunteers for Joe Biden’s presidential campaign in a state where more than 3 million early ballots already have been cast. “This conversation and this contact is really important.”

With that pep talk and a friendly reminder to wear gloves and a mask, more than a dozen women hit the streets here this weekend for the first time in eight months, after being grounded by the pandemic as the Biden campaign made its organizing efforts entirely virtual.

“I can’t tell you how excited I am to see full-bodied people,” Eberly said. “You aren’t just heads on Zoom.”

The morning gathering in a driveway on Wedgewood Drive would have been entirely unremarkable during any other election season. But this year, it speaks to an anxiety-producing question being quietly raised by some veteran Democratic organizers: Can a virtual strategy replace an on-the-ground operation, typically the backbone of a winning Democratic campaign?

Build your own road to 270 electoral votes with CNN’s interactive map

These waning days of the presidential race are framed by the starkly different approach that President Donald Trump and Biden are taking to the coronavirus. Their differences extend far beyond policy and directly into the nuts and bolts of campaign mechanics. Until recently, Biden’s team has done most all of its work virtually. Some organizers are doing their jobs remotely, from different states.

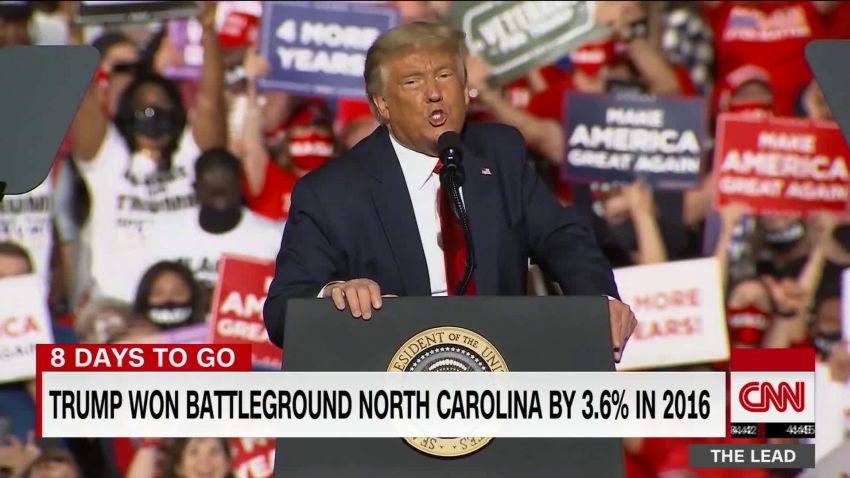

Trump has gone full speed ahead, with multiple rallies a day at the center of his game plan. Trump Victory, a joint operation of the campaign and the Republican National Committee, boasts of knocking on millions of doors, but it declined repeated CNN requests to observe its neighborhood efforts.

Advisers to Biden have embraced the contrast in their approach to campaigning during a pandemic, yet they ultimately gave the green light to socially distanced canvassing. They approved face-to-face, get-out-the-vote efforts for the final weeks of the race in more than a half-dozen key battleground states, including North Carolina, even as cases and hospitalizations rise.

North Carolina has more than 1.3 million new registered voters since 2016, which political strategists on both sides say makes organizing efforts even more important than in states with more static populations. Turnout, of course, holds the answer to the outcome of every election. But the methods of finding voters and getting them to the polls are being watched particularly closely this year, with much of the campaign being conducted virtually.

‘They get to see me’

The Biden campaign’s decision to return to on-the-ground get-out-the vote efforts was welcome news to Eberly and Scarlett Hollingsworth, her canvassing partner, both of whom spent much of the weekend knocking on doors in hopes of tracking down voters to ask about their plans to cast their ballots.

“I’m just so energized to be actually able to talk to voters face-to-face, because in the past that’s always been how you judged how things were going,” Eberly said. “Having been doing phone banking and other things digitally and virtually, I don’t have that same sense this year.”

Both women make clear that they supported the Biden team’s decision to not allow door-knocking or face-to-face canvassing throughout the spring and summer in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. But they also said they wonder whether they’ve lost ground to Republicans, who revived their efforts months ago.

“The phone is great, but a lot of people don’t answer numbers they don’t really know,” Hollingsworth said. “So you miss those conversations that you might have had at the door.”

Helen Woods, who has invested hours talking with voters on the phone or through Zoom meetings for much of the year, said she was delighted when she learned she could grab a clipboard and start knocking on doors again in critical Charlotte neighborhoods.

“It’s just wonderful to be able to actually see somebody, talk to somebody – and they get to see me,” Woods said, stopping to talk for a moment before setting off on her volunteer shift. “I think it’s reassuring for them to see this little white-haired person coming to their door and saying it’s OK to vote, and it’s OK to be open about being Democratic.”

Trump motivates both sides

In the stretch of the race, Trump remains the biggest motivating force of this campaign – for supporters and opponents alike. He visited North Carolina twice in four days last week alone, including at an evening airport rally in Gastonia.

Four years ago, he won Gaston County, just west of Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County, by more than 30 percentage points. To win the state again, he’s trying to repeat – or increase – those margins.

“He energizes the crowd itself. It’s just awesome,” said Jim Gallagher, a Republican member of the Gastonia City Council who was on hand for the Trump rally last week. “I’m getting people calling me, asking me how they can help. These are people who have never done anything for a campaign..”

Jonathan Fletcher, chairman of the Gaston County Republican Party, said the President energizes his core supporters and attracts new ones by visiting his county. He said the Trump rallies are the best part of the campaign’s get-out-the-vote efforts.

“Here and everywhere he goes – that’s the point of him going all of these places,” Fletcher said. “If we can run up the score here, we’re going to be able to balance out anything they can do in Mecklenburg.”

Yet there is little question that Trump’s presence also motivates his Democratic detractors. His visits draw considerable attention, as did one to the state on Sunday from Vice President Mike Pence, which only shined a brighter spotlight on the administration’s handling of coronavirus.

Barack Obama narrowly carried the state in 2008, a victory that Democrats here still fondly remember. That winning campaign was built through traditional on-the-ground organizing efforts.

This time, Biden and Trump are locked in a tight race for the state’s 15 electoral votes. For Trump, the state is critical in his path to winning 270 electoral votes. Biden has far more routes to the White House, but a North Carolina win would all but certainly block Trump’s reelection.

For Biden and other Democratic candidates on the ballot, the level of turnout among Black voters is critical.

“There’s plenty of people we know who vote in every election – those people we’re not going to worry about,” said Terry Brown, a Democrat who is running for a Statehouse seat. “But the people who are on those fringes, we must make sure that we’re speaking to them in a way to give them a reason to get out and vote.

Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles, a Democrat, said she thinks about organization and turnout efforts every day and wonders if enough work is being done. She acknowledged the pandemic creates a set of unknowns for traditional political organizing, particularly among Black voters.

But she believes Democrats – and Republicans and independents who have soured on the President – have a bigger motivating force that will overtake any particular organizing effort.

“People are living through a very difficult time in their lives,” Lyles said in an interview. “This time has been framed by Covid and the President’s lack of response for it. And that’s why I think people are going to come out to vote.”