Pedro Almodóvar is in Madrid at his production company El Deseo (The Desire). El Deseo could not be a more fitting name: desire has been at the heart of his films. All sorts of desire: for love, sex, justice, acceptance and truth. Behind him are DVDs, books and a phalanx of awards. He has five Baftas, five Goyas and is the only Spanish director to have won two Oscars (best foreign film in 1999 for All About My Mother and best original screenplay for Talk to Her in 2002).

He is sitting on a purple chair, wearing a pink jumper, his hair quiffed into a punky white meringue. You suspect that every colour in Almodóvar’s life has been carefully handpicked – just as in his films. His back is ramrod straight, his manner both warm and regal. Almodóvar is a man used to being in control, and today there is a translator (despite his fluent English), assistant and publicist at his service. When I met Almodóvar previously, in Madrid in 2004, he was tense throughout our conversation, and only began to relax after the interview. At the end, he gave me a copy of a calendar I had admired, featuring pictures he had shot on location. He signed it “Things are simpler and yet more complicated”. Somehow, it seems to sum up his films and worldview perfectly.

Things are rarely as they first appear in Almodóvar’s films. Transformation is a recurring theme in Parallel Mothers as it is in all his work: characters are changed by surgery, mishaps, performance (his protagonists are often actors by profession) and gender fluidity.

The young Almodóvar wanted to observe and celebrate the new Spain, then in the midst of La Movida Madrileña (known as the Movement or the Happening), Madrid’s counter-cultural flourishing that developed in the transition to democracy and in opposition to all that had gone before. La Movida was punk, promiscuous, queer, anti-clerical and rampantly hedonistic – just like Almodóvar’s films.

“When I was making my first films, everyone around me was really young and wanted to live their lives and enjoy themselves. The first couple of films I made, Pepi, Luci, Bom and Labyrinth of Passion, had their genesis in a time. For me that was apolitical.” Being apolitical at the time was effectively a political statement, he tells me over Zoom.

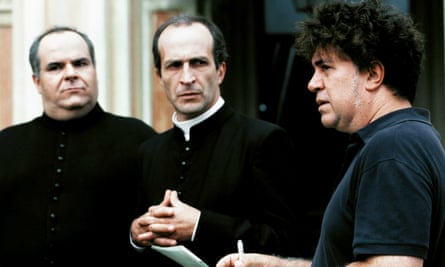

So he made films that celebrated the present. Almodóvar didn’t just satirise nuclear families as his compatriot Luis Buñuel had done a few years earlier – he obliterated them. In early films such as Dark Habits, Law of Desire and What Have I Done to Deserve This? he created his own families of pregnant nuns, transgender prostitutes, mariticidal wives, drug‑dealing sons, and bullying patriarchs destined to be seen off with a cosh to the head in the first act. His films played out in their own moral universe: women tended to go unpunished for crimes committed against men who’d simply got their just deserts; a man who rapes a comatose woman is portrayed sympathetically in 2002’s Talk to Her because he loves her (the rape awakens her and allows her to live again). Almodóvar has the ability to shock people of all political persuasions.

Yet behind all these cinematic celebrations of the present was a ghost. When Almodóvar started making films, he promised himself one thing: his movies would give the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco the ultimate two-fingered salute. They wouldn’t explicitly condemn his fascist politics; they wouldn’t ridicule the general who ruled Spain for 39 years until his death in 1975; they would simply act as if he had never existed. As a director, he says, he didn’t want to think about fascism and Franco back then: “It was my way of getting revenge on him. But it didn’t mean to say I’d forgotten.”

But now Almodóvar has had a change of heart. He is speaking in long, fiery sentences with few pauses – a very different passion from the high-camp passion of his younger days. He is not only now willing to discuss Franco, he thinks it is essential. Now, he says, is the time to remember Franco lest his victims be forgotten. And Parallel Mothers, which received a nine-minute ovation when it premiered at the Venice film festival last September, does just that.

In one way it is a typical Almodóvar film: vibrant, sexy, subversive and emotional. A pregnant woman in her 40s (played by Almodóvar regular Penélope Cruz) befriends a pregnant teenager, Ana (the wonderful newcomer Milena Smit), in the maternity ward, and all kinds of craziness develops. Alongside this runs a very different story. Cruz’s character Janis believes a mass grave outside her local village contains the bodies of those executed by Franco and the fascist Falange party in the Spanish civil war, including her great-grandfather. She is fighting to have them exhumed. It is an issue that is currently being discussed with some urgency throughout Spain, and one that Almodóvar felt he had to tackle before it was too late.

Only 19,000 of the estimated 114,000 civilians who disappeared during the 1936-39 civil war, and throughout Franco’s dictatorship, have been recovered since his death. Many are thought to have been dumped in mass graves – and time is running out to get to the truth. “The whole issue of these common graves from the civil war is becoming more pressing as the days go by,” Almodóvar says. “Those remains have been in the mass graves for so long that they may not even be identifiable any more when they are exhumed. There may be no family members left to identify them.”

Born in 1949, Almodóvar grew up in rural, traditional La Mancha. His father ran a petrol station, his mother a bodega where she sold her own wine. His parents hoped he would become a priest and sent him to a religious boarding school at the age of eight, where he developed a hatred for religion and a love of cinema. After watching Warren Beatty in Splendor in the Grass he realised he was attracted to men (though for many years he was bisexual). In 1967, he moved to Madrid, against his parents’ wishes, to escape poverty and become a film-maker. For 12 years he worked as an admin assistant at the phone company Telefónica to support himself financially.

I ask how Franco’s reign affected him as a child. “When you’re a boy, your life is different. I was very happy when I was young. I wasn’t aware really of what was going on around me. I was aware we didn’t have any money, but life is full of treasures when you are young – and they are not material treasures.”

He became aware of Franco when he was sent away to school. Franco aligned himself with Spain’s Catholic church to forge a dual dictatorship, and it didn’t take Almodóvar long to realise he would never become a priest. “The schools were run by priests and that was a nightmare.” He says he was lucky – he was not sexually abused, but plenty of his friends were.

This is a subject he addressed in the 2004 film Bad Education. “So many boys were abused by these priests in all the schools. As well as the impoverished education, I spent the whole time at school terrified that the priests would molest me. All my life since then I’ve fought against that Judaeo-Christian education. That’s the thing I most deplore in all my childhood.”

As a teenager, he started to understand how oppressive life was. “I felt afraid of the ‘Grey Uniforms’ as we call them, the national guard. The policemen were the ones repressing us. I realised that there were films we could never get to see in Spain, there were books that never got to us, there were things we couldn’t buy. I remember the total darkness of that time.”

Then came the liberation of La Movida. The late 1970s and 1980s was a wonderful time to be young, he says. Madrid became known as “the city that never sleeps” – everything was possible, nothing taboo.

The two women at the heart of Parallel Mothers could represent the two Almodóvars – of yesteryear, and today: Cruz’s Janis and the younger Ana sum up the debate dominating Spain in a simple, impassioned exchange. Ana tells Janis you have to focus on the present to live a fulfilling life; a furious Janis replies you can only make sense of the present if you understand the past – and to fail to do so is a betrayal of your ancestors.

After Franco’s death the political parties of Spain forged the Pact of Forgetting. The pact stated that in order for there to be a smooth transition to democracy, there would be no prosecutions for those responsible for human rights violations or similar crimes committed during the Francoist era. Not surprisingly, it was controversial. Today, Almodóvar says the notion of forgetting is nonsense. “You can demand it in a symbolic way. What you can’t do is ask people to forget. The families of victims of the civil war will never forget them. Remembering is part of the soul of who we are.”

Back then, many on the left believed there would be another coup without the pact, not least because many Franco loyalists were still active in politics. Indeed, there was an attempted coup by some police and military officers in 1981, four years after the pact was signed.

Almodóvar believes that the pact was pragmatic at the time, but should have been challenged as soon as democracy was re-established. “After the left had been consolidated in political power, we should have gone back to the whole scene of the mass graves and all those crimes from Franco’s dictatorship that were still unresolved. What Franco did was bury those people so deep into the ground that he almost denied their very existence.”

Last year, the leftwing government approved a new Democratic Memory bill to tackle the legacy of Franco’s dictatorship and the civil war that preceded it, with measures to honour those who suffered persecution or violence. If it comes into law it will create two remembrance days to honour the victims and the exiled, and an official registry of the victims will be set up. It will also promote the search and exhumations of victims buried in mass graves.

Does Almodóvar think the Democratic Memory bill has come too late? “I’m not sure if it’s too late, but better late than never.” He points out that the left still doesn’t think the new law goes far enough because it will not redress all the property and assets that Franco stole from the victims. But Almodóvar also worries that Spain is returning to the darkness. As with so many countries, the populist far right is on the rise, and politics is becoming increasingly polarised.

The far-right Vox is now the third-largest political party in parliament, and Almodóvar is alarmed by its influence. Hard-won freedoms and truths are already being reversed, he says. “What they are doing is revisiting and revising what happened. They are telling the civil war history from their ideology, which is totally Francoist in nature.” Vox’s historical revisionism blames the Second Republic, which brought democracy to Spain in 1931, for the civil war, rather than Franco’s military coup. “It’s really important for people to be able to make this distinction between the truth and fake news.” He pauses. “The expression ‘fake news’ falls short of what they are doing with these lies.”

Does he fear a return to fascism in Spain? “I’d love to say I don’t fear that there may be a return of fascism, but I think that might be going too far. We certainly have to understand the importance of the fact we have Vox now in politics. That we have a far-right party which is now the third political force here is unbearable, and unacceptable.”

The bigotry that is reflected in the rise of Vox can now be seen in everyday life, Almodóvar says. “The last 30 years we never saw the homophobic attacks we’re starting to see on the streets of Spain now. This party is seriously homophobic, anti-women, extremely racist. I wouldn’t say I’m afraid, but I am very worried about them.”

For all its labyrinthine plotting and breathless romance, Parallel Mothers is probably the closest Almodóvar will ever get to a polemic: a simple plea to honour the victims of Franco. “There is a moral debt now in society to the families of these victims who were fellow citizens fighting to defend our democracy, which is why it’s so timely to have this theme in my film today.”

Almodóvar is not only aware that time is running out to redress the crimes of Franco; he knows that if he hadn’t addressed the issue now, it might well have become too late for him, too. He has been conscious of ageing and obsessed with death ever since he was a young man. Before Parallel Mothers, he made Pain and Glory, a film about an ageing director Salvador Mallo (played by Antonio Banderas) in an existential and physical rut, suffering migraines, backaches, depression, tinnitus, the works. “Without film-making my life is meaningless,” Salvador says. Almodóvar has said the movie is autobiographical.

The difference between Salvador and him is that the fictional director was suffering writer’s block. By contrast, Almodóvar has spent the past quarter century creating classic after classic. He consistently draws phenomenal performances from his regular actors. Most of them are women. Some have gone on to become huge Hollywood stars, such as Cruz (he once said only Cruz could make him reconsider whether he is gay), Antonio Banderas and Javier Bardem. There is an astonishing sensuality in his films: everyday acts such as chopping vegetables or making a cup of coffee leave you purring with pleasure. His stories are as rich as the colours and imagery he uses to illustrate them.

Over the years his movies have remained as outre as ever, but they have become more serious and affecting. His genius has been to make the outlandish believable. And again he pulls it off in Parallel Mothers.

What gives his films their heart is his love for his protagonists and their optimism. However tough their lives, they tend to pull through in one way or another, their hope still intact. There is a profoundly moving scene at the end of Parallel Mothers that unites past and present, victims and survivors. Action triumphs over quiescence, remembrance over forgetting, hope over fear.

I ask whether Almodóvar shares the optimism of his characters. He has been so solemn talking about Franco’s legacy, but finally I see a familiar twinkle in his eye. “Yes. Although the current times we are living through, the economic circumstances, the political circumstances, the health circumstances are not the best of times any more, every single morning I get up I make myself feel optimistic because you always gain from it.”

He allows himself a smile. “Yes, for me, optimism is something I am an absolute activist about.”

Parallel Mothers is in UK cinemas from Friday.