SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

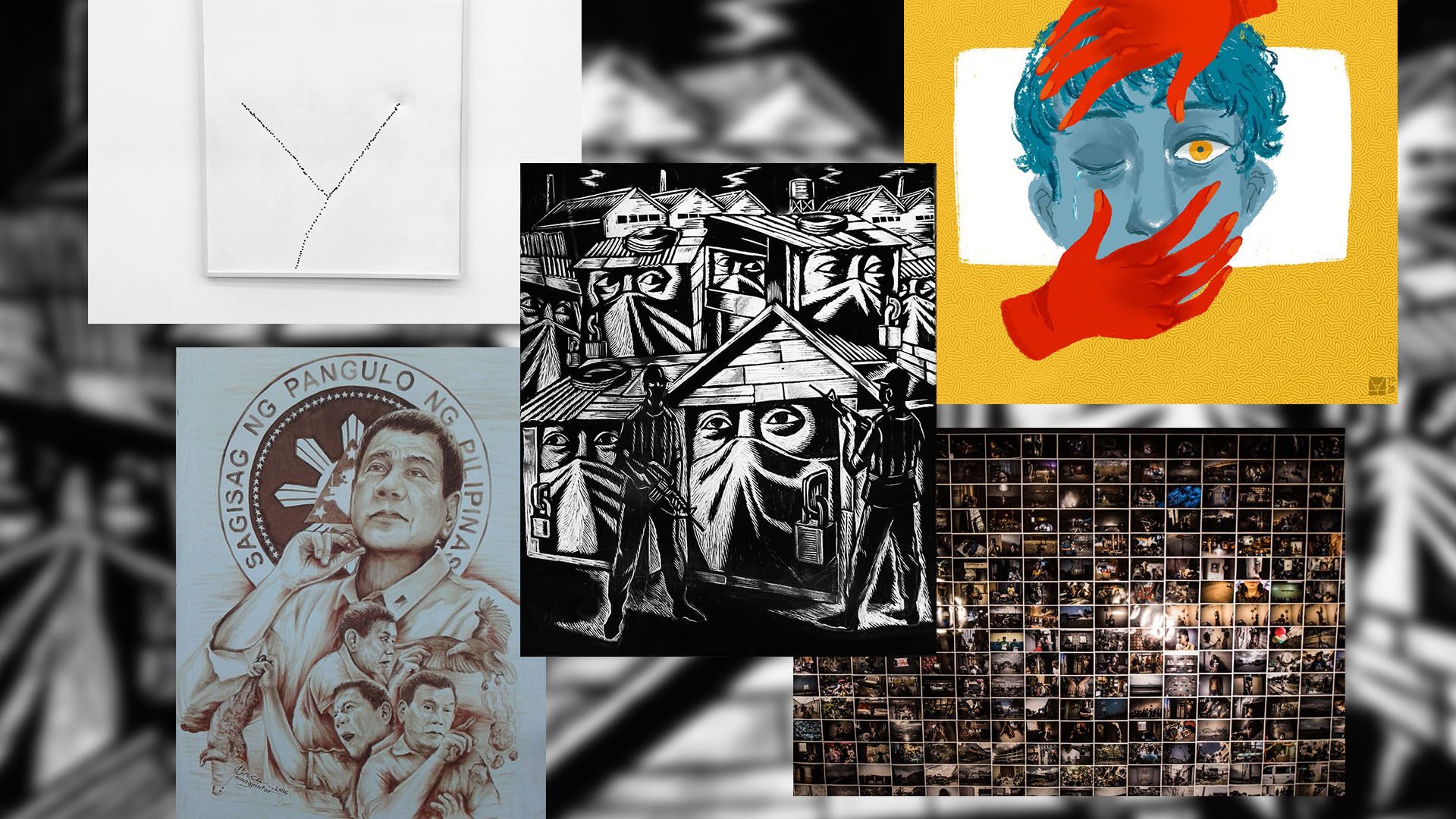

MANILA, Philippines – President Rodrigo Duterte’s six years in office has been an interesting time for Philippine art.

His term has seen 15 new National Artists – among them pop culture icons such as actress Nora Aunor, writer Ricky Lee, composer Ryan Cayabyab, editorial cartoonist Larry Alcala, and filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik.

Tahimik once showed friendliness toward the President, taking a “symbolic selfie” with him using a bamboo “camera” as he was given his National Artist award in 2018.

“I like your distancing of the Philippines away from America. I support you on that,” the filmmaker said then.

Years later, though, Tahimik, along with other artists, would sign a manifesto condemning the extrajudicial killings enabled by Duterte’s war on drugs.

Support on the one hand, criticism on the other – Tahimik’s small interactions with the President are perhaps an example of the duality of the Filipino art world’s relationship with the head of state.

Duterte has enjoyed high satisfaction ratings throughout his term, a telling sign of his enduring popularity.

The idolatry surrounding Duterte gave rise to many tribute art pieces – portraits of the President made by adoring fans.

Japanese artist Ayumi Endo first painted Duterte in 2016 “to fight against the black propaganda in the Philippines, which was widespread across the country at that time,” according to her website.

For “Touch and See” – Endo’s art project to make 3D pieces for the visually impaired – it was Duterte’s face that she chose to depict, placing its 3D form at the center of a canvass surrounded by other Filipino symbols: the national flag, Manny Pacquaio’s boxing gloves, a durian fruit, a tarsier – a simplistic collage of Filipino culture as told from a foreigner’s eyes.

In what is perhaps one of the more extreme acts of devotion, one artist even used his blood to depict Duterte.

Elito Circa, also known as Amang Pintor, regularly uses blood and hair in his work. He painted his portrait of Duterte in October 2016. At the time, he said, “Bilib talaga ako sa kaniya. Minsan negatibo siyang magsalita, pero parang kaibigan lang ‘yan na naiintindihan mo kahit iba pa ang pananalita niya.“

(I believe in him. Sometimes he speaks negatively, but he’s just like a friend that you understand even if he speaks differently.)

The portrait rendered in blood early on in Duterte’s term faintly foreshadows what the President’s rule would turn out to be – and what other artists would go on to criticize in their work.

RealNumbersPH, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency’s unitary report on the drug war, said that 6,252 people died in anti-illegal drug operations between July 2016 and May 31, 2022.

While the report claimed to show the “pinakabago at tunay (newest and truest)” numbers on the drug war, human rights groups estimated the total death toll to reach 30,000, including victims of vigilante-style killings.

Many artists turned to their craft to respond to this hallmark of Duterte’s rule, giving Filipino art at this time a strong undercurrent of protest.

At the 2018 Art Fair Philippines, writer and composer Erwin Romulo, photojournalist Carlo Gabuco, composer Juan Miguel Sobrepeña, lighting designer Lyle Sacris, and sound engineer Mark Laccay set up a chilling installation called “Ang Mga Walang Pangalan (Those Who Don’t Have Names).”

In a dim room lined with grisly photos of drug war victims, lights flickered and a voice recording of a drug war orphan was played as the actual chair her father was shot in was set under a spotlight at the center.

In an online exhibit by the University of the Philippines’ human rights research project Dahas, various artists explored the hypocrisies of Duterte’s war on drugs.

Artists also spoke up against the anti-terror bill, signed into law by Duterte in July 2020 and enabling an anti-terror council to arrest and detain suspected terrorists without warrant. The law’s critics say that it could be used to target political opponents, activists, and dissidents.

“Artists fight back,” read the hashtag on social media.

In her piece “Female Fighter,” Nikki Luna made a statement against Duterte’s silencing of critics, as well as his misogynistic remarks, with M4 bullet holes on a white aluminum panel, forming the shape of a woman’s womb.

In July 2021, as the country heaved under the Duterte government’s poor pandemic response, artists were among the loudest voices, criticizing the endless cycle of militarized lockdowns and calling for mass testing and better treatment for healthcare workers, even raising funds for frontliners themselves through their art.

Satirical cartoonist Tarantadong Kalbo was among the artists who were moved by the government’s inadequate handling of the pandemic. As a COVID-19 surge raged on, he released a now-ubiquitous image called “Tumindig (Stand Up).” In the image, an army of anthropomorphic hands bow down, looking like Duterte’s signature fist bump. Among them, one hand rises up, a fist in the air, a sign of protest.

Before long, other artists joined in, editing the image to include their own takes. Eventually, even non-artists joined “Tumindig’s” art army of raised fists, painting a picture of how, in the face of oppression, ordinary citizens become artists, too.

“I guess the message is to not be afraid of speaking out, of standing up for what is right, even if it feels like you’re the only one doing it,” Tarantadong Kalbo said at the time. “All it takes [is] one drop to start a ripple.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.