There has been a lot of talk about tactical voting in the British general election - there are even apps and websites to help people vote tactically.

But will they actually use them?

Is talk of tactical voting just that - talk?

Or has Brexit become such a dominant issue in British politics that voters will consider using all kinds of means - including tactical voting - to ensure their side of the Brexit argument wins the election?

A political scientist involved in running the British Election Study- the biggest in depth study of British voter behaviour, which has been on the go for 55 years - thinks it will play a marginal role in Thursday's vote.

Dr Jonathan Mellon of the University of Manchester said Brexit has made voters more willing to vote for other political parties that back their side of the Brexit argument.

"Generally about 40% of voters are considering one or more of the other parties on their side, so Conservative voters are willing to consider the Brexit Party, and then Labour voters are willing to consider the Lib Dems, Greens.

"And the other way around as well - Brexit party voters are willing to consider Conservatives and the Greens and Lib Dems are willing to consider Labour."

There may be a willingness to vote tactically, but there is more to it than that.

It needs knowledge of the last election result - in particular, who finished second.

"To tactically vote you need to know who won in the constituency last time, and you need to know who came second so you can coordinate around the potential challenger to go and take a seat", said Dr Mellon.

He added: "And what we found in the data is that people generally know who won their seats in 2017, but they don't have that good knowledge of who came seconds in leave seats.

"Generally, fewer than 30% of voters can currently name the second place party in 2017, and that's going to make it very difficult, even if they want to tactically vote, to actually go through with it".

Britain has a peculiar voting system - first past the post, as it's known.

Each of the 650 constituencies elects one member, and the person who gets the most votes, wins the seat.

And that often means the winners get less than 50% of the vote. Which in turn means that a party can win a majority in parliament without getting anywhere near a majority of the votes cast.

(Neither Labour nor the Conservatives have attained 50% or better in vote share).

So David Cameron got 36.9% of the vote in 2015, but won 51% of the seats in parliament - 331 - giving him a majority of 13.

Theresa May was heavily criticised for losing that majority in her 2017 snap election, designed to get a mandate for Brexit.

But under her leadership the Conservatives won 43% of the national vote - far more then Cameron. But the way the votes fell in individual constituencies sealed her fate; her near 43% of the vote translated into 48.9% of the seats in parliament - 318 - a loss of 13 compared to Cameron.

The polls now put Boris Johnson's Tories on about the same national share of the vote as Theresa May got in 2017.

Yet they are suggesting a Conservative majority - and a big one in the case of the large scale MRP poll published ten days ago.

It said the Conservatives could win 359 seats - up 42 on Theresa May's result, but with exactly the same share of the national vote. (The YouGov MRP was the only poll to predict a hung parliament in 2017: It is due to publish an update on Tuesday night).

Clearly the national trend is less important than what happens on the ground in individual constituencies. And that's why campaigners on both sides of the Brexit divide have focused on a small number of seats they think will decide the election.

According to the pro-remain New European newspaper, a poll for anti-Brexit group Best for Britain suggests the Tories could win 345 seats, leading them to conclude that 35 seats hold the key to stopping a Conservative majority. And the group claims that a switch of fewer than 2,500 votes in each constituency would be enough to stop a Conservative candidate winning.

Read More:

Farage says Brexit Party will not challenge Tories in 317 seats

Neil calls out Johnson ahead of leaders' debate

Parties clash over Corbyn claim NHS is 'on the table' in trade talks with US

They calculate that just 41,000 tactical votes could decide the outcome of the election. And that is in a country with an electorate of some 46 million.

Another tactical voting site - Remain United - set up by anti-Brexit litigant Gina Miller, focuses on 36 seats, highlighting how tactical voting could unseat prominent Brexiteers like Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, and former leader Iain Duncan Smith.

The decision on what party candidate to back is based not on who won last time, but on current polling data.

The key point about tactical voting is that it all comes down to how votes get cast in each individual constituency. The idea is to gather together the votes of all those in a constituency who don't vote for the party that usually wins there.

For example, if you are in a constituency where the Conservative candidate won the seat with 40% of the vote, then clearly there is an anti-conservative majority in the constituency.

But this majority must come together to back a single candidate in order to oust the Conservative. And organising that is a lot harder than it sounds (and it sounds pretty hard).

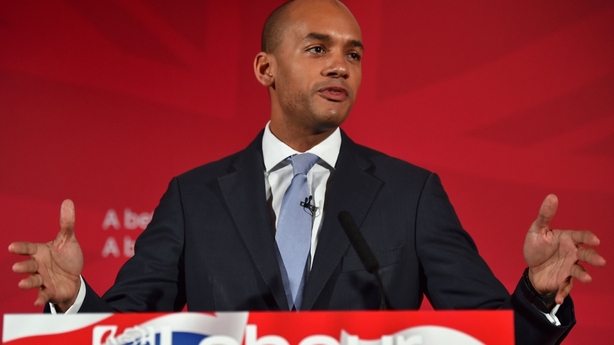

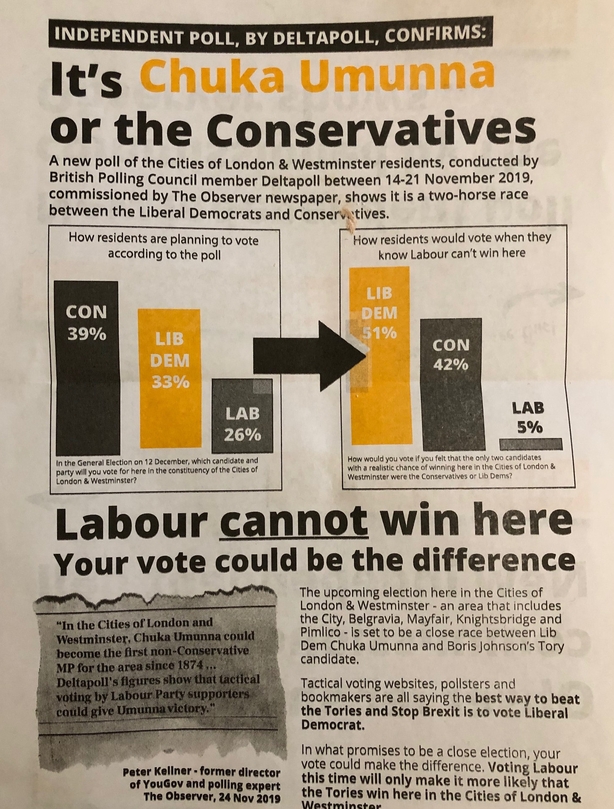

In the constituency in which I live - the Cities of Westminster and London - the Liberal Democrats are trying to convince voters to get rid of a conservative MP by backing their candidate Chuka Umunna (a former Labour MP who defected to the Lib Dems over Brexit).

Using a tactic employed by Lib Dems across the country they are using bar charts to try and persuade anti-conservative voters that the Lib Dem candidate is the only one who has a chance of unseating the Conservative.

The appeal to the voters is "you may not like the Lib Dems, but if you really want to get rid of the Conservatives, in this Constituency, we are your only realistic choice".

A more subtle form of tactical voting is being attempted by online platforms like Swap My Vote.Uk, which attempts to match voters in one constituency where their preferred candidate has no chance of winning, with voters in another constituency who have the opposite problem.

The website facilitates an informal "vote swap" pact between paired up voters in different constituencies.

The problem is, it relies entirely on trust between two people who have never met, live in different parts of the country, and support opposing political parties.

You agree to vote for a party you don't like, and hope that the other person keeps their end of the deal. And because voting is secret (and it’s illegal to use a camera phone in a polling station) you have no way of checking.

The British Election Survey has been asking people about the sources of information they use to make election decisions.

"In our data we asked people who they thought would win in each constituency", said Dr Mellon.

"And then we followed up with asking them where you're getting your information from, and only about 6% of voters mentioned tactical voting websites. So it's a pretty minority pursuit, going on these websites, even though they've received a lot of attention in the media".

The British electorate has become increasingly volatile in its behaviour.

Where once voters stuck with parties through thick and thin, over the past four decades British voters have become far more inclined to switch votes on individual issues.

Back in the 1960s, when the British Election Survey started, about 13% of voters switched parties between one election and the next.

In 2015 that figure had reached 43%. "If you look all the way back from 2010, 2015 to 2017, fewer than half of the voters voted for the same party every time in these elections" said Dr Mellon.

"So you have the majority of voters who really are swing voters now, and that's a huge change: it means there's a lot more possibilities and a lot more uncertainty about how the outcome will be at every election", he said.

But the survey data finds that the big switch may have already happened - back in 2017 - and the dividing issue was Brexit.

The switching that is going on now is between parties on the same side of the Brexit divide - Brexit Party voters moving to the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats moving to Labour and vice versa, depending on the constituency.

This is how the Conservatives could, according to some pollsters, end up with a runaway majority.

The Remain or Remain oriented parties could end up splitting the remain vote more than the leave supporting parties. And in tight constituencies, that could make the difference, which is why pro-remain activists see tactical voting as their best chance to stop Brexit at this election.

The Conservative’s hardball approach to the Brexit Party has paid off, with Nigel Farage withdrawing candidates in every constituency where the Tories hold a seat.

He claims they are helping the Conservatives make inroads into Labour constituencies in the North of England that voted leave in 2016.

That is viewed sceptically by Professor Geoffrey Evans of Oxford University (and the British Election Survey).

He said: "I was in Stoke two nights ago, where I'm from, as it happens (doing interviews for the Survey), and all three constituencies are a battleground. In the two constituencies where there was a Brexit party candidate I felt reasonably confident that Labour would probably just about hang on.

But, in the other constituency, where there wasn't a Brexit party candidate, it's clearly going to be Tory. And so the deal that Farage sprung by saying we won't stand against you, is not that helpful to them (the Conservatives) because they're not so much stealing hardcore Labour votes as all the other people in the constituency who may have left Labour, a long time ago.

"Those people are tempted by the Brexit Party, which let's face it, don't carry the historical baggage of Conservatism. For some people at least, in an area where Mrs [Margaret] Thatcher was demonised as the person who destroyed manufacturing industry, it's easier to vote Brexit Party, than it is to vote Tory."

If that is true across the whole of the "Red Wall" of traditional Labour seats in the North of England, then the Brexit Party could be weakening rather than enhancing the prospects of a Conservative majority, and with it the prospects of Britain leaving the EU on 31 January.

And it shows one of the problems of tactical voting as a concept: it’s too cerebral - it doesn't take enough account of the human factor; of how much people in some parts of England, Scotland and Wales hate the Conservatives more than they want Brexit; or how some people who fear Brexit are even more fearful of Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister.

And then there is the anecdotal evidence emerging of the impact of social media on that emotional, gut reaction type of political decision making, with journalists and others noting that in some working class estates in the midlands and north voters are expressing extreme dislike of Jeremy Corbyn.

Perhaps the ultimate tactical voting game has been one we cannot see, one that has already been played out over the past two years with a precisely targeted, but well hidden campaign to undermine the appeal of the Labour leader in naturally Labour voting areas.

Like much else about this bizarre election, it's hard to come to a definitive conclusion on the importance of tactical voting; it could be a crucial factor in turning the direction of the election, and with it the course of Brexit: or it could be just too complicated to organise in any meaningful way.